May 2025

The New Bicycle Blueprint:

A Plan to Make New York a World-Class Bicycling City

Over the past 50 years, New York has transformed into a city where hundreds of thousands of people ride a bike every day. But our streets have so much more potential. It is time to make New York a world-class bicycling city.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Imagine a city where an eight-year-old can ride their bike home from school…

…where an 80-year-old can get to the senior center and the supermarket by e-bike, staying active and mobile in their community despite aching joints,

…where a hopeful newcomer can make ends meet at their job because they travel by bike, saving money every month,

…and where riding a bike — whether for weekend exploration or an invigorating commute — is safe, accessible, and joyful, whether you live on Staten Island or in East Harlem.

All of this is possible.

With relatively flat terrain, low car ownership, unmatched density, and superior access to mass transit, New York City is already primed for the widespread adoption of bicycling.

The next step is giving every New Yorker reliable access to a high-quality, connected bike lane network, bike share system, and safe storage space for their bike — so that people in every corner of New York, from all walks of life, and at all levels of ability, can hop on a bike whenever it makes sense for them.

If we do all this, we could easily grow the number of trips taken by New Yorkers on bikes every day, from around 620,000 today to one million daily trips by 2030.

The benefits of an effortlessly bikeable city would be extraordinary: calming the chaos of our streets, expanding our economy, and making new corners of our city accessible for housing, industry, and commerce — all while giving every New Yorker access to a convenient, affordable, and healthy way to get around.

Cleaner air, safer streets, longer life expectancies, less congested roads, improved public health, substantial cost savings, and even fewer potholes — it all starts with a bike and a safe place on the streets to ride it.

The Goal

Transportation Alternatives calls on New York City’s leaders to create reliable access to a high-quality, connected, all-ages-and-abilities bike lane network, a bike share system, and safe storage space for bicycles — to meet the pent-up demand for bicycling and make bicycling possible for all New Yorkers.

Our goal: Empower New Yorkers to take one million daily bike trips by 2030 and realize New York’s potential to be a world-class bicycling city.

Building for All Ages and Abilities

Image credit: NACTO Designing for All Ages & Abilities

An all-ages-and-abilities (AAA) bike network is a designation used by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) to demonstrate how bike infrastructure can be designed to welcome people with less experience riding a bike or those who may not be seen as, or consider themselves, traditional cyclists.

Building for all ages and abilities means considering how to make bike infrastructure safe, comfortable, and attractive to the widest variety of people. Broader than simply building a bike lane network, the goal is to build a bike lane network that offers biking as a mobility option to people of all ages and all levels of cycling experience, as well as those with physical, visual, auditory, and mental disabilities who wish to ride.

AAA bike networks incorporate the needs of children and seniors, people who use adaptive handcycles, cargo bicycles, bike share, and e-bikes, and non-traditional or often-overlooked cyclists, such as low-income riders, women, people of color, workers, and people with disabilities.

Historical Precedent

In 1993, Transportation Alternatives published Bicycle Blueprint: A Plan to Bring Bicycling Into the Mainstream in New York City. The 162-page document laid out a plan for expanding New York City’s bicycling infrastructure, including building bike lanes, greenways, and bike parking, teaching New Yorkers how to ride a bike, and reducing the risk of bike theft and injury. It was a first-of-its-kind plan that envisioned a future where cycling was convenient, safe, and effortless in a city where it was long considered a risk-takers’ hobby.

In 1997, following the recommendations of the Blueprint, the City of New York published the NYC Bike Master Plan, which laid out a vision for a 900-mile connected network of bike lanes, greenways, and bike-friendly bridges, as well as bike parking, riding education, bike theft deterrence, and standardized street designs.

In the second term of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the City of New York would accelerate these plans, embarking on a large-scale effort to popularize bicycling in the city. The goal was twofold: increase access to biking while making biking safer.

Building America’s first parking-protected bike lanes in 2007 created a safe entryway to cycling for New Yorkers, especially those new to cycling. The introduction of street-closure events, such as Summer Streets in 2008, and of a public bike share system in 2013 gave New Yorkers the opportunity to try biking on city streets and to access a bicycle without upfront costs or indoor bike storage.

Over time, the City of New York increased its efforts, adding bike access to key bridges and more high-quality lanes. Protected bike lane installations have ramped up from a cumulative 25 miles installed from 2007 to 2011, to 148 miles installed in the last five years.

Half of the protected bike lane miles installed since 2007 have been built in the last five years.

The result of these efforts was astounding. Researchers found that every mile of protected bike lane that the City of New York added to streets created 1,100 daily bike trips, and 15% to 20% of these added bike trips replaced vehicle trips. This results in a per-mile reduction of roughly 140,000 to 190,000 vehicle miles traveled in automobiles every year.

Between 2007 and 2024, the number of people who commute by bike in New York City tripled. Public bike share expanded massively, from approximately 8.6 million rides in its first full year of service in 2014 to 44.5 million rides in 2024 — a fivefold increase. 13% of all New Yorkers used a Citi Bike at some point last year.

Bicycling has gone from a high-risk form of employment and niche hobby to a mainstream option for more New Yorkers to get around. But there is still so much more potential on our streets.

The Problem & the Opportunity

Despite this progress, the vast majority (98%) of New York City’s streets lack a protected bike lane.

The protected bike lane network is geographically limited, with nearly half of all existing protected bike lanes located in Manhattan. Citywide, the majority of bike lanes are unprotected and unappealing to most New Yorkers who might otherwise consider riding a bike.

The protected network is still relatively limited and fragmented. Protected lanes are often blocked, disconnected, or end abruptly on hazardous streets. Many bike lanes “give up” at the intersection, leaving cyclists unprotected in the most dangerous place on the street. While there are more protected bike lanes than ever before, a network is only as strong as its weakest link, and one harrowing intersection is enough to make someone swear off riding a bike forever.

Choosing to bike can also be out of reach for people who cannot store a bike at home — especially in a city known for density, small living spaces, and crowded conditions. There are two simple solutions to this problem employed by cities around the world: citywide access to bike share and secure bike parking.

However, New York City’s bike share system is the only one in the country that operates without public funding. Without that funding, bike share access is limited to half of the city. Secure on-street bike parking is practically nonexistent, and even unsecured racks can be few and far between. Only a small fraction of the bike parking spaces that exist are protected from the elements or from theft.

As a direct result, many New Yorkers who might benefit from biking — whether that benefit is related to health, transportation costs, mobility, or the joy of human-powered transportation — do not bike.

This is not a problem of culture, climate, topography, or geography — it is a problem of infrastructure and access.

In surveys, the vast majority of New Yorkers report “feeling unsafe” as their chief reason for not riding a bike, and this is true across racial demographics and income brackets. For New Yorkers who wish to bike but don’t, the second most reported reason is having nowhere to store a bike.

These perceptions bear out in the data: nearly every person killed on a bike in the past decade was killed on a street without a protected bike lane.

These perceptions bear out in the data: nearly every person killed on a bike in the past decade was killed on a street without a protected bike lane.

Bike lanes are frequently blocked, with obstructions occurring on average every 500 feet. Between 2020 and 2024, the number of 311 requests for blocked bike lanes nearly tripled, with New Yorkers filing a request every 28 minutes on average. This declining enforcement of bike lanes has consequences: in a 2023 survey, only 30% of New Yorkers rated bike safety positively, down from 46% in 2017.

Individual risk of cyclist death or injury is also increasing as the pace of infrastructure fails to keep up with changing conditions on the road, including rising car use in New York City, and the growing weight and horsepower of vehicles on the roads.

For years, as the City of New York built more bike lanes and more New Yorkers rode bikes, the likelihood of being killed or seriously injured on a bike declined. But since 2018, though the number of people riding bikes and the miles of bike lanes built continue to rise, the risk of being killed or seriously injured on any given ride has started to rise under changing conditions. The number of vehicle miles traveled, the average weight of vehicles on the road, and the average horsepower have all skyrocketed in recent years. As a result, between 2018 and 2023 alone, the risk that a person on a bike was killed or seriously injured on any given trip rose by 22%.

Today, there is an enormous opportunity for leadership. An actionable plan is essential to New York’s future as a world-class bicycling city, where bicycling grows and people on bikes feel safe.

New York has an opportunity to build a safe, connected network of protected bike lanes anchored by secure bike parking and a world-class bike share network to give millions of New Yorkers the chance to ride a bike. In a city of 8.3 million people, everyone deserves an abundance of safe options to get around and the freedom to choose.

The Vision & the Plan

Transportation Alternatives has a vision of a New York City where bicycling is as easy, accessible, safe, and efficient as taking the bus or subway — no matter what corner of the city you live in — and where everyone who wants to hop on a bike feels able to, regardless of their age, ability, or neighborhood.

This vision can be achieved with a plan: steady and focused action to complete a high-quality bike network and extend reliable access to a bicycle to every New Yorker who wants or needs one.

A high-quality bike network is:

Safe for all ages and abilities. Lack of access to a safe route is the number one reason New Yorkers choose not to ride a bike. On wide, arterial streets, a safe route is one that is protected from moving traffic and parking with hardened infrastructure guarding both the lane and the intersection, and is wide enough for conventional and electric bikes to share. On smaller, residential streets, a safe route is one that limits egress, discourages through-traffic, and controls vehicle speeds with hardened infrastructure. Both are kept clean and clear with automated enforcement of bike lane and parking violations and fast, responsive towing.

Connected. Every bike lane in New York should connect to another bike lane. No bike lane should ever end abruptly or dump cyclists into hazardous traffic. Each lane should be matched with a corresponding lane traveling in the opposite direction on an adjacent parallel street or, where that is impractical, be two-way. Missing a turn should not require backtracking on an unsafe street.

Accessible. Every New Yorker should live within a quarter-mile — around five short blocks, or a five-minute walk — of the bike lane network. Every bridge in New York City should have bike access in a separated bike-only lane.

Reliable access to a bicycle requires:

Citywide reach. A citywide bike share program, supported by City funding, could make reliable bikes accessible in every neighborhood. Ensuring electric-assist bike share bikes are included in a citywide expansion would mean that New Yorkers who are older or disabled also have reliable access to a bike that works for them. Bike racks on buses and subways, along with secure bike storage at stops and stations, would mean that you can use a bike to help reach your destination even if it’s too far to ride alone.

Affordability. Biking should be the most affordable form of transportation, with limited maintenance and a moderate cost to own or rent. To make bikes even more affordable, especially for low-income New Yorkers, commuter benefit cashout programs that allow employer parking benefits to be used for bike purchases are essential, as are City-funded citywide bike share access and government rebate or subsidy programs for e-bike purchases.

Security. A lack of secure, reliable storage is one of the most common reasons many New Yorkers don’t ride a bike or stop biking. In addition, an increasing number of New Yorkers who ride e-bikes are turning to dangerous gas-powered mopeds due to a lack of storage space for safe charging. Neighborhoods across the city should have secure on-street bike parking, protected from the elements and theft, safe e-bike charging, and access to bike share.

If we can achieve this vision, then our air will be cleaner, our streets will be safer, our population will be healthier, and more of us will have access to opportunity. There might even be a little more joy in every New Yorker’s life.

Who Rides a Bike In New York City?

Access to Citi Bike has also proven to be a great equalizer in determining who rides a bike: the majority of Citi Bike riders are people of color, nearly half of the women who ride a bike use Citi Bike, and nearly half of Citi Bike trips are made by women. Some 17,000 Citi Bike members access the system through a reduced-fare subsidy program for NYCHA residents and SNAP recipients, more than one in five Citi Bike riders is a student, and 37% have an income below $75,000. The total number of Citi Bike trips has increased by 440% in the last decade.

In New York City, 42% of adults — approximately 2.7 million New Yorkers — ride a bike at least once a year. 16% of adults report riding a bike at least once a week and 24% at least once a month.

New Yorkers take more than 230 million bike trips a year. As New York builds more bike lanes, these numbers are growing: the number of adults riding at least once a month increased by more than 40% between 2010 and 2020.

Each year, bike share is responsible for an increasingly large number of people on bikes. There were nearly 45 million Citi Bike trips last year, approximately 35,000 bikes were available on city streets, and 13% of New Yorkers rode a Citi Bike at least once. During peak summer months, average daily Citi Bike ridership is similar to that of the New York-New Jersey Port Authority of Trans-Hudson (PATH) train.

In 2022, 42% of New York households reported owning one or more bikes. Since many households have multiple family members with bikes, there are four bikes for every five households in New York City, and New York City households collectively own around 2.6 million bikes.

These bikes are increasingly using electric-assist. Today, one in ten New Yorkers who own a bike owns an e-bike, and citywide, 70% of Citi Bike rides are made on Citi E-Bikes. In the hilly Bronx, that number climbs to 90% of Citi Bike rides. Citi E-Bike rides are longer by half a mile. Since Citi Bike re-introduced electric bikes to their fleet in 2020, New Yorkers have taken 70 million electrified rides, and 29 million of those rides, or 40% of all Citi E-Bike trips, were taken in 2024 alone.

Bikes are also increasingly a route to employment, with more than 70,000 New Yorkers relying on bikes to do delivery work and more than half of Citi Bike riders using bike share to commute.

Who Would Benefit?

Building a high-quality protected bike lane network that is accessible to all New Yorkers would benefit everyone who rides a bike or wishes to, and the city as a whole. This includes pedestrians and drivers, people of color, women, families, people in low-income neighborhoods and transit deserts, and older New Yorkers.

Protected bike lane networks increase safety and feelings of safety — a virtuous cycle that makes people less likely to be killed or injured while cycling, and more likely to ride because they feel safer.

Every Person Who Rides or Wants to Ride a Bike Would Benefit

Research shows that access to bike lanes, and in particular, a high-quality connected network of bike lanes, makes biking safer and more enjoyable, which in turn leads to more people biking. For every New Yorker choosing to ride a bike, every trip improves their health, saves them money, and offers mobility no matter their access to transit.

More than 40% of New Yorkers who wish to ride a bike but do not do so say they avoid cycling because of the lack of bike lanes. The next most common reason is a lack of safe places to park or store a bike. New Yorkers who live within a quarter-mile of a bike lane are significantly more likely to ride than those who live a mile or more away.

Researchers have found that cities with protected bike lane networks have 44% fewer cyclist fatalities and 50% fewer serious injuries compared to an average city. This safety boosts ridership: increasing the reachable area of a low-stress bike lane network by one mile increases ridership by as much as 14%.

However, when bike networks are disconnected, people are less likely to try bicycling and more likely to choose another mode. A landmark study in 2017 examined the relationship between piecemeal protected bike lanes and a connected network and found that, while ridership generally increased with every added bike lane and every additional mile of bike lane improved safety, it was the bike lane network connections that improved safety most of all.

Pedestrians Would Benefit

Almost all of us spend part of every day as pedestrians — whether we’re walking to our destination, a car, a bike, or the train — and creating a high-quality bike network would benefit every New York City pedestrian. Adding bike lanes improves pedestrian safety, both in general and on the specific streets where they are installed.

When protected bike lanes are added to New York City streets, we see declines in the number of drivers speeding, the number of overall crashes, and most importantly, the number of pedestrians killed or injured in crashes. This is because protected bike lanes increase the visibility of pedestrians and calm reckless driving.

This effect is multiplied by the fact that, when protected bike lanes are added to city streets, more people ride bikes, many of whom are drivers and for-hire vehicle passengers shifting trips out of cars. In the U.S., the average protected bike lane sees bike counts increase 75% in the first year alone. In New York City, these results are even more pronounced: shortly after a protected bike lane was installed on Prospect Park West, bike counts increased by 190%. After one was installed on the Brooklyn Bridge, bike ridership grew by 88%. This means that every bike lane reduces the number of car trips on city streets at large, improving the overall air quality and decreasing the crash risk of all streets, even ones without bike lanes.

Bike lanes also reduce conflicts between people on bikes and pedestrians by creating a safe and appealing space for bikes on the road. In New York City, the installation of protected bike lanes has been shown to directly and dramatically reduce the number of people who bike on the sidewalk. Protected bike lanes reduced the number of people on bikes riding on the sidewalk by 97% on Prospect Park West, by 84% on 9th Avenue, and by 68% on Columbus Avenue.

Drivers Would Benefit

Creating a high-quality connected network of protected bike lanes would benefit New Yorkers behind the wheel because every new bike lane reduces traffic congestion, both by calming traffic and by shifting trips out of private and for-hire vehicles.

Researchers have found that New York City’s protected bike lanes have actually sped up traffic for drivers by bringing order to chaotic streets. This is in part because protected bike lanes streamline New York City’s varying road widths to the recommended standard, and in part because protected bike lanes are often installed in conjunction with turn lanes, which minimize delays by giving drivers room out of the way to wait to turn.

Even just a 3.7% drop in vehicle miles traveled reduces congestion by 30% — which means that shifting only a small number of trips out of cars provides huge gains to people in cars.

People of Color Would Benefit

Creating a high-quality bike network would benefit people of color in New York City. Surveys have found that the majority of people of color report feeling uncomfortable riding in conventional painted bike lanes and are statistically more likely to ride when protected bike lanes are available.

Evidence of this potential can be found in e-bike use, as e-bikes allow low-exertion, long-distance transportation in places the public transit network does not reach. While Citi E-Bikes are popular citywide, they are most popular in the Bronx, where hills are common, many of the city’s slowest bus routes are located, and subway access is limited. In 2024, 90% of Citi Bike rides taken in the Bronx were made on Citi E-Bikes.

Citywide, 70% of interborough Citi Bike trips were taken by e-bike, and people using Citi E-Bikes take longer trips on average and connect to transit more compared to conventional Citi Bike users. For New Yorkers living in transit deserts, combining access to e-bikes — through subsidies and an expanded bike share program — with a protected bike lane network, creates a needed transit option and commuter connector.

People Living in Low-Income Communities Would Benefit

Creating a high-quality bike network would benefit New York City’s low-income communities, as people living in low-income communities are 76% more likely to ride a bike when offered a protected lane.

Of all available methods of transportation, riding a bike is the most cost effective, in terms of cumulative costs. However, under current conditions, people living in low-income communities are exceedingly at risk: 43% of cyclist fatalities and 45% of serious injuries occur in high-poverty census tracts that make up just 28% of city streets.

People of color in New York are at a higher risk of being struck and killed in all traffic crashes, and make up a disproportionate number of those killed on bikes. Communities of color are also more likely to be transit deserts, rely on buses, and have a high rate of air pollution. Shifting trips out of private cars and for-hire vehicles and into bikes can address these various issues in a singular way — increasing mobility for people living in transit deserts, reducing the traffic congestion that often slows New York City’s buses, and cleaning the air.

Women Would Benefit

Creating a high-quality bike lane network would benefit women in New York City, who are statistically less likely to ride when protected bike lanes are not available and who make up less than a third of New York City bike commuters, despite being a majority of the population. While citywide bike ridership grew 8% from 2018 to 2021, ridership declined by 3% among female cyclists.

In New York City, women outnumber men — 52% to 48% — but men are 83% more likely than women to bike at least once a month, and 127% more likely to bike at least once a week.

The most common reason for New York City women to say they don't bike is that they don't feel safe, and dedicated cycling infrastructure like protected bike lanes has been shown to directly increase women’s willingness to ride bikes. Women are less than half as likely as men to feel confident riding on all roads with traffic, and more than half say access to bike lanes and bike paths would increase their riding.

Women often pay a “pink tax” on transportation — relying on car services because walking or public transit feels unsafe. Making biking feel safe for women with a network of protected bike lanes is a step toward alleviating this burden.

Families and Children Would Benefit

Creating a high-quality network of protected bike lanes would benefit families and children, who often need door-to-door transportation in a city where car ownership is uncommon, driving is onerous, and crossing the street is often unsafe. Today, four in five children’s trips to school in New York City are made without a car.

The ability for children to safely bike alone is a boon to independence and public health, and as the city has built more protected bike lanes, families have responded with enthusiasm. The number of children walking and biking the full distance to school increased by 44% between 2013 and 2017. The expansion of double-wide bike lanes — making room for cargo bikes — would allow these numbers to grow to include large families and children too young to ride.

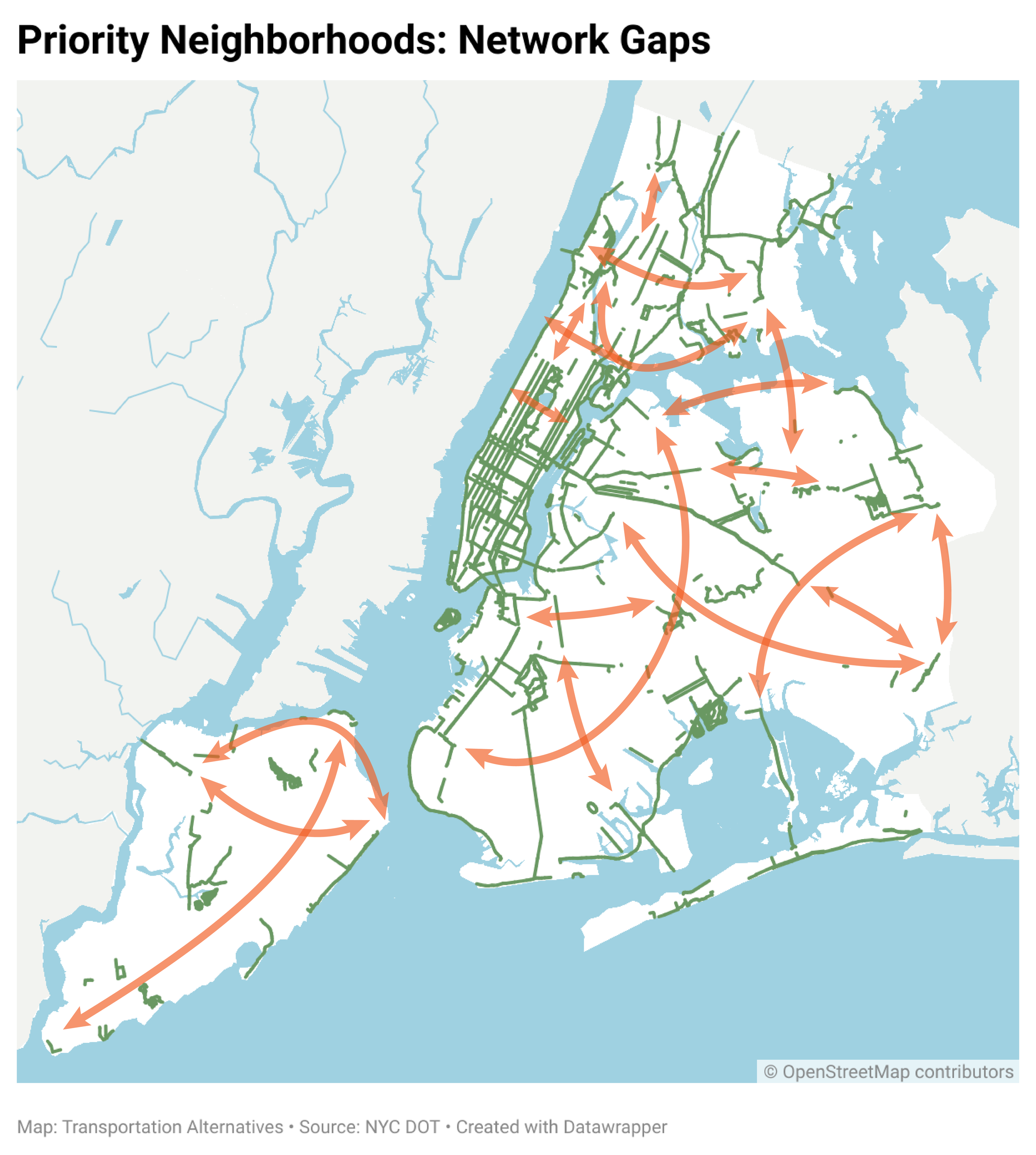

Children are disproportionately at risk in all traffic crashes, and child traffic fatalities are strongly concentrated where the bike network lags outside Manhattan, especially in Vision Zero Priority Areas in Central and South Brooklyn, Central Queens, and the South Bronx. In these neighborhoods, where the majority of school-age children are people of color, the streets outside schools have a higher rate of speeding and crashes.

Older New Yorkers Would Benefit

Creating a high-quality bike network would benefit older adults, who are at higher risk in case of a crash, and who commonly have impact-related mobility issues that limit walking and visual-related mobility issues that limit driving. One in four older New York City voters owns a bike, and one in seven rides at least once a month.

E-bike use is especially increasing among older populations. Wider bike lanes and other accommodations for e-bikes further benefit older New Yorkers, allowing them to ride long distances and up hills, and maintain mobility and social engagement while aging.

Bike lanes protect older New Yorkers even when they are not biking, by improving overall street safety. New York City’s protected bike lanes have reduced the number of older New Yorkers killed or seriously injured while walking by nearly 40%.

People Living in Transit Deserts Would Benefit

Creating a high-quality protected bike lane network would benefit people living in transit deserts by providing efficient routes to destinations, and to public transit when it is located farther away than a reasonable walk.

As low-income communities are often transit deserts, e-bike access is especially valuable. Low-income Citi Bike members use Citi E-Bikes 75% of the time.

New York City’s Economy Would Benefit

Bicycling infrastructure is also a job creator, creating more jobs than any other type of road project. Researchers have found that every $1 million spent on building bike lanes creates 11.4 jobs within the state, whereas building vehicle lanes only creates 7.8 jobs per $1 million spent.

This economic benefit extends to the business community. In New York City, sales revenue generally rises faster on streets with bike lanes. For example, after a protected bike lane was installed on 9th Avenue in Manhattan, sales at local businesses rose 49%, and when one was installed on Union Square North, retail vacancies fell 49% while only falling 5% elsewhere in the borough. Researchers have found that cyclists tend to spend more at local businesses because they are significantly more likely to engage with their surroundings, browse store windows, and make unplanned purchases. Drivers, who are traveling at much faster speeds, tend to be more focused on navigating the roadway and are more likely to pass through neighborhoods without stopping.

New York City as a Whole Would Benefit

Simply put, building a high-quality bike network would benefit New York City. Building bike lanes reduces street congestion, pollution, transit crowding, traffic crashes, commercial vacancies, the economic burden of public health, and increases business revenue.

Researchers have found that every mile of protected bike lane added to New York City streets creates 1,100 daily bike trips. This benefits public health, the environment, air quality, personal mobility, and the economy — because 15% to 20% of these added bike trips replace vehicle trips, resulting in a reduction of roughly 140,000 to 190,000 vehicle miles traveled in automobiles. Every trip shifted out of a private car or for-hire vehicle reduces air pollution, carbon emissions, and the cost of road wear, crashes, and congestion.

Models from Other Cities

London

London provides a replicable model for New York City. In 2024, London saw 1.33 million daily bike trips in a city with an almost equal population size, twice the square mileage, and on average, less hospitable weather for cycling.

London’s effort demonstrates how achievable the goal of one million daily bike trips for New York City should be.

In 2018, the City of London embarked on an effort to expand bike ridership within the city limits. To achieve this, London introduced safe bike lane standards, tripled its protected bike lane mileage, and targeted under-invested neighborhoods to maximize the number of Londoners living within biking distance of the bike network. And perhaps most notably, London created a massive system of bike parking, including 30,000 secure “cycle hangar” spaces, which are protected from theft and weather, 20,000 bike parking spaces at transit stations, and another 150,000 on-street spaces.

This effort was wildly successful. Not only did London grow daily bike trips by 13%, but the city saw a wealth of other benefits, including a 22% reduction in particulate matter and a 25% reduction in cyclist fatalities and serious injuries.

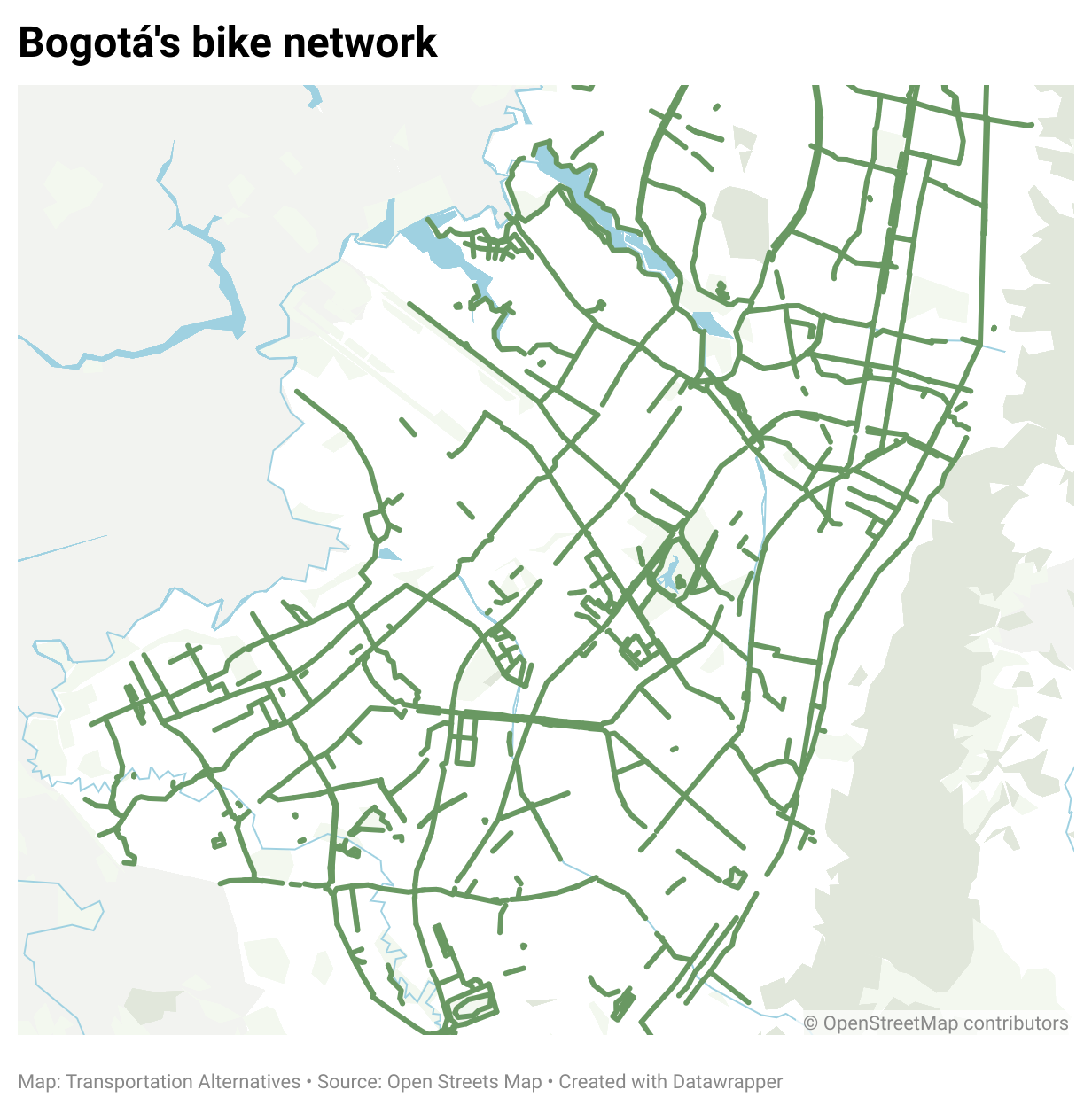

Bogotá

Bogotá provides a replicable model for New York City, with a similar-sized population and double the square mileage. By building a protected bike lane network alongside growing Ciclovía — a once-weekly closing of city roads to cars — Bogotá transformed cycling from a functional tool for residents living in poverty to a common form of transportation and celebration.

First launched in 1974, Ciclovía is a program that shuts down city streets to cars once a week, on Sundays, and opens them to people walking and biking. Over the past 50 years, Bogotá has grown the program massively, from closing 5 miles of city streets for a few hours to closing 75 miles of streets for the day. In a city of 9 million, some 2 million residents of the city participate every week. The program has demonstrated significant public health outcomes, including reduced air pollution and increased perceptions of safety. For every dollar invested in Ciclovía, the city saves up to three dollars in medical care.

In 1998, only 0.6% of trips in Bogotá were taken by bicycle. Then, the city built 180 miles of protected bike lanes in just three years. By 2019, the bike lane network had been expanded to more than 330 miles — and 9% of trips were made by bike. Today, 900,000 bicycle trips are made in Bogotá every day.

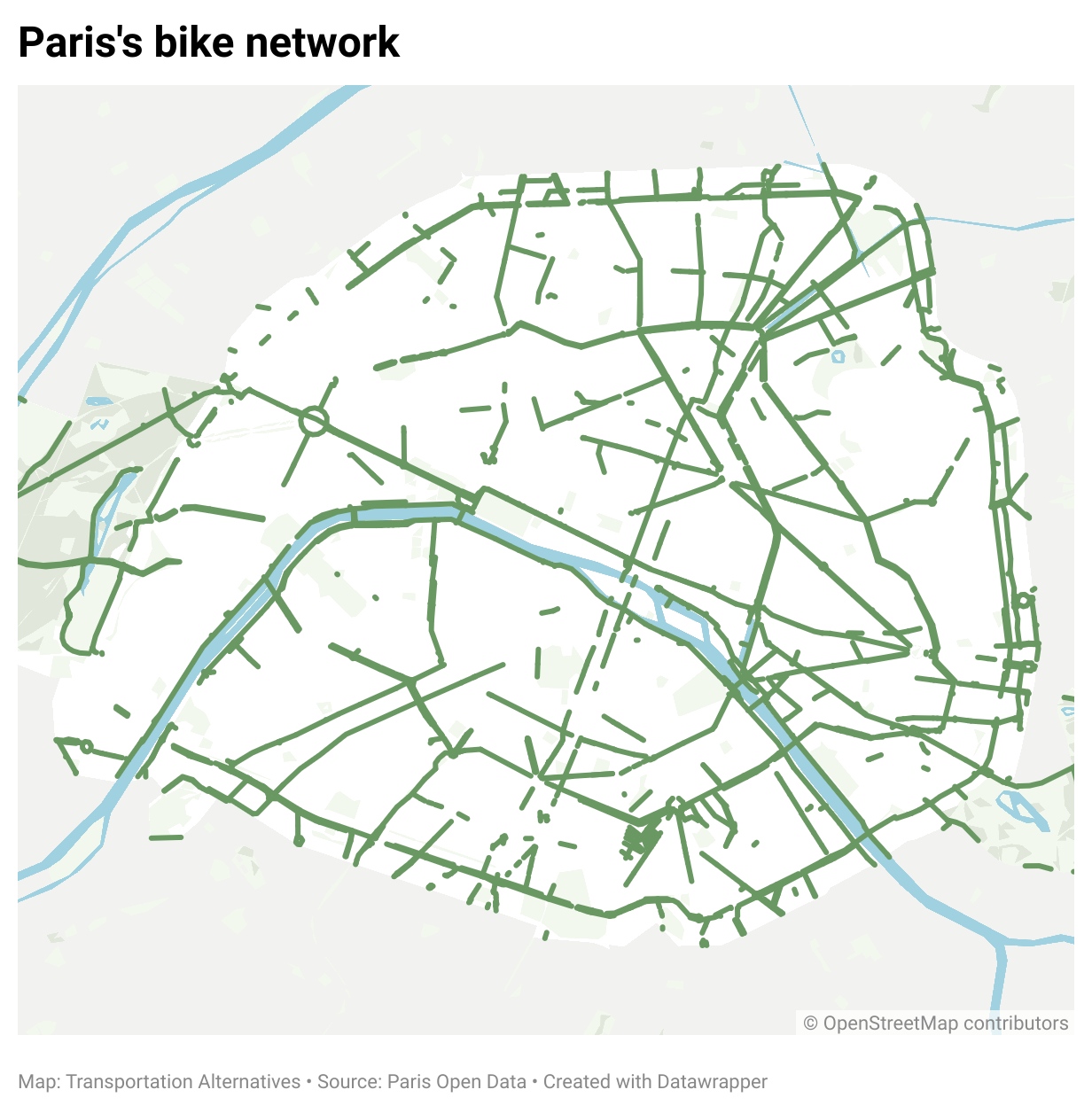

Paris

Paris also provides a replicable model for New York City of how to grow bike ridership by redesigning streets and supporting a citywide bike share system with City funding. In Paris, more than 11% of trips within the city center are made by bike — outpacing car use nearly three times over — while in New York City, just 2% of trips are made by bike and 28% are made by car.

Paris’ effort demonstrates how achievable it would be to shift trips out of cars.

Over the last decade, Paris expanded its bike share system, added over 600 miles to its bike lane network, and is in the process of adding tens of thousands of bike parking spaces. The city also actively discouraged car use by creating car-free zones in the city center, increasing one-way streets, reducing parking spaces, and raising the price of SUV parking.

This effort has been wildly successful. Between 2010 and 2024, Paris grew bicycling trips from 3% of all trips to 11.2%. As a result, the city saw a wealth of other benefits, including a 40% drop in air pollution and a 34% drop in injuries and fatalities.

Paris’ bike share system provides an especially notable model for New York. There are twice as many Vélib' shared bikes available per resident in Paris as there are Citi Bikes available per resident in New York — with one bike share bike available for every 121 Parisians compared to one for every 242 New Yorkers. In 2024, Parisians and visitors took 49 million trips on the Vélib' bike share system — 5 million more trips than on Citi Bike — despite Paris having one quarter of New York City’s population. This is the potential of a citywide bike share system, supported by City funding.

The Five Borough Bikeway

In 2020, the Regional Plan Association published The Five Borough Bikeway, a model of how New York City’s bike network could look. It is the first step toward a complete, connected, accessible system of bike lanes — safe for all ages and abilities.

If created, this 425-mile network of protected, continuous, high-capacity, priority bike lanes would boost bike ridership, public health, and air quality while offering new paths to mobility to millions of New Yorkers living in transit deserts or with interminable commutes. This plan lays out the spines from which every neighborhood bike network could grow.

Image credit: Regional Planning Association

Recommendations

Transportation Alternatives recommends that the City of New York set a goal of one million daily bike trips by the year 2030, joining the ranks of truly world-class bicycling cities around the world from Paris to Bogotá.

To facilitate that goal, New York must: (1) build a connected network of protected bike lanes, (2) advance generational infrastructure projects that support and accommodate cycling growth, (3) maintain the bike network as a high-quality resource over time, (4) facilitate reliable access to a bicycle for everyone who wants or needs one, and (5) implement policies that encourage people to ride bikes.

Build a Connected Bike Lane Network

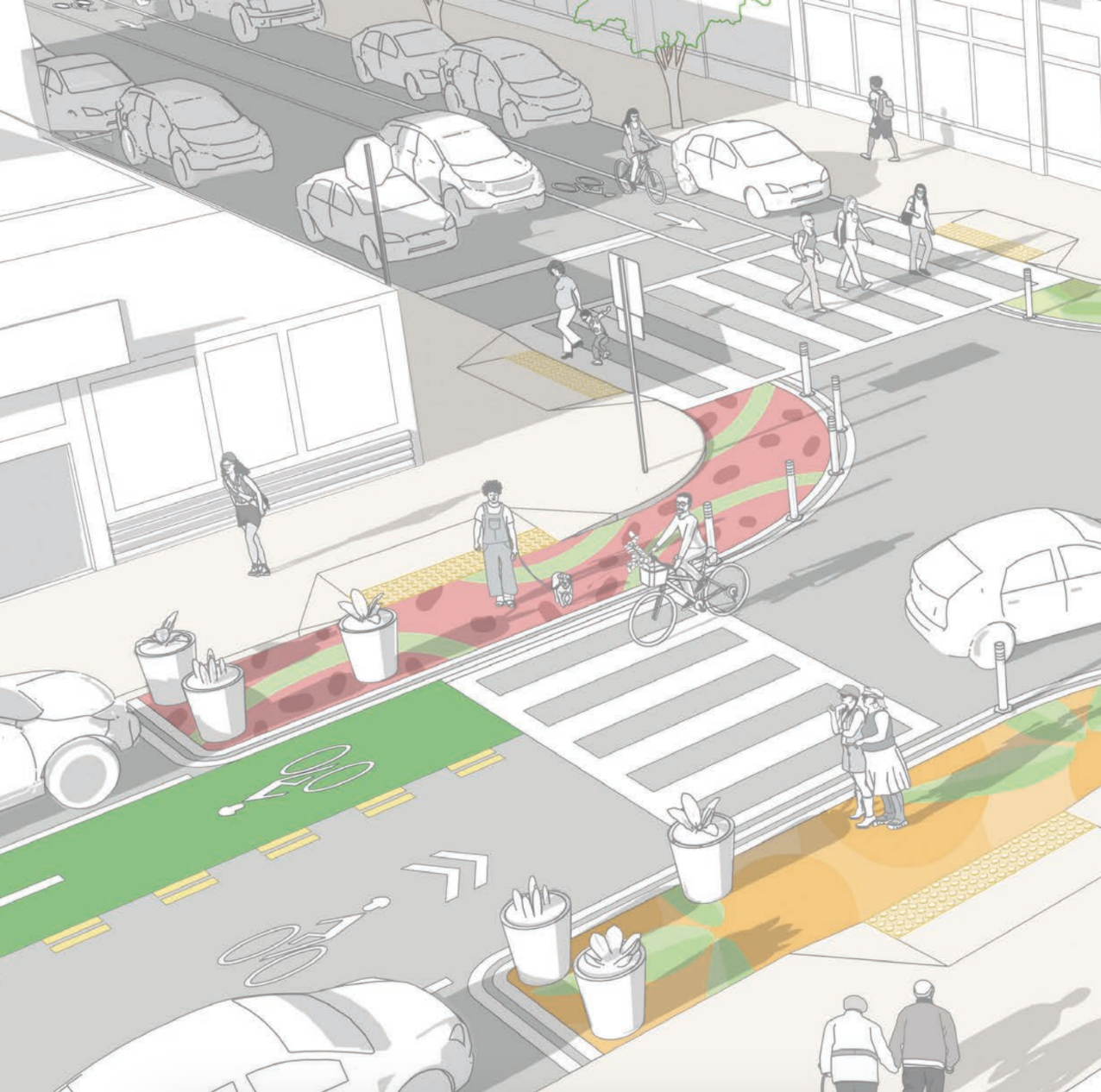

A bike lane network is a connected grid of bike lanes that are safe for all ages and abilities, made up of protected lanes, greenways, and low-traffic streets, and accessible within a quarter-mile (around five blocks) of every New Yorker’s home. Building a connected bike lane network requires understanding bicycle routes as a large-scale system of lanes and intersections, where both the larger network and pieces that make up that network require consideration and coordination.

Network Recommendations

Map a bike lane network that allows every New Yorker to access a protected bike lane within a quarter-mile of their home and construct 50 miles of the network annually until complete, starting with broken connections in the existing network and communities with high rates of ridership but limited access to the network.

Fast-track the launch of the “Bicycle Network Connectivity Index,” which is required as part of the NYC Streets Plan by 2028.

Develop a template for low-traffic “bike boulevards” that can be implemented on narrower residential streets, with hardened infrastructure to control egress and vehicle speed, and map out a network of low-traffic streets citywide where connectors are needed in the larger protected bike lane network.

Add protected bike lane connections, clear street markings, and wayfinding between all existing bike lanes so that no bike lane ends abruptly, leaving cyclists stranded and confused.

Examine the bike lane network for opportunities to create new bike lanes traveling in the opposite direction of existing bike lanes on adjacent parallel streets, or two-way bike lanes on one-way streets, so that missing a turn never requires backtracking on an unsafe street.

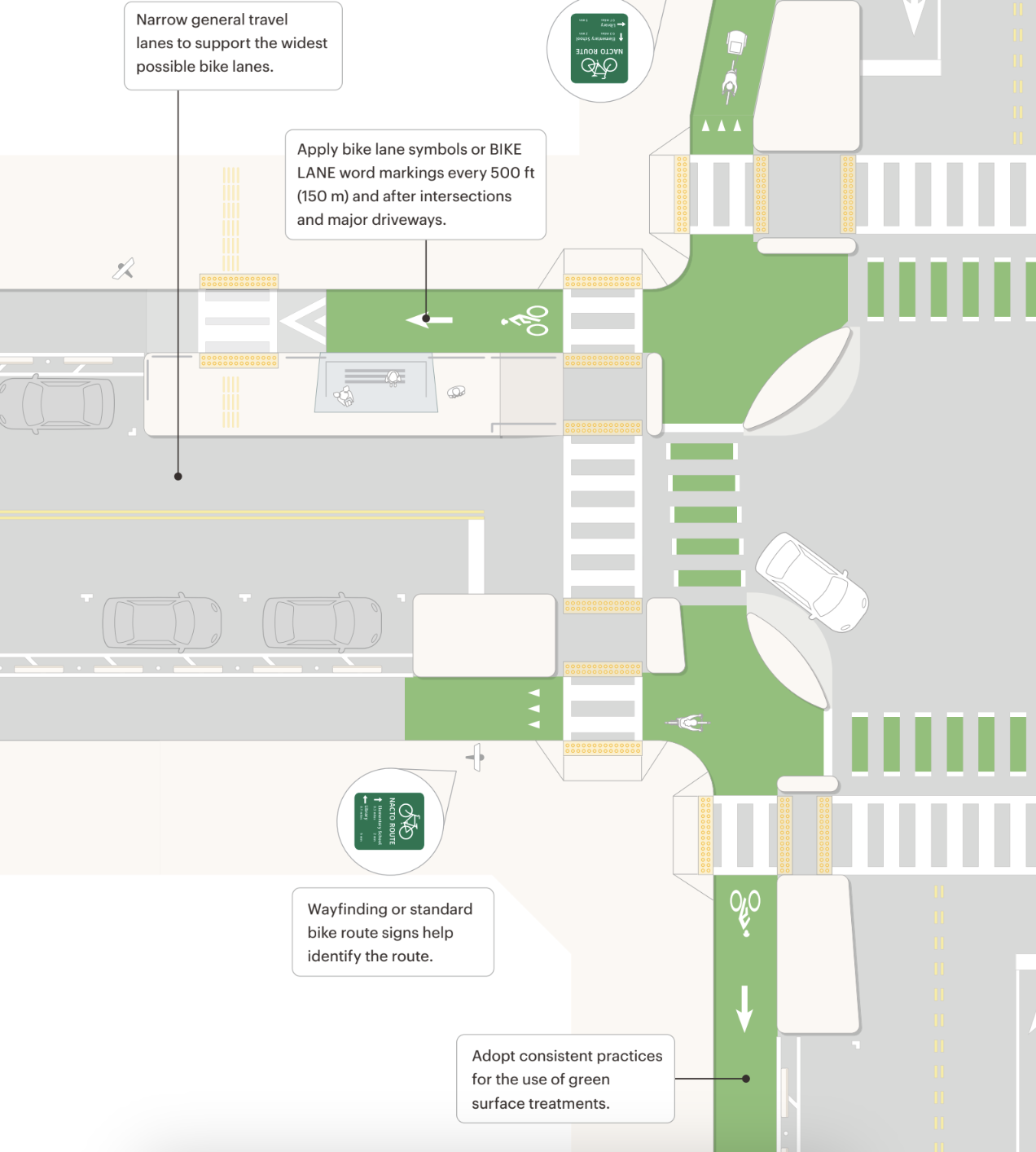

Image credits: NACTO Urban Bikeway Design Guide

Accelerate the build-out of greenways, starting with missing connections between the existing bike lane network and greenways.

Create a greenway bridges program within the Department of Transportation focused on planning, designing, and building bike and pedestrian bridges, overpasses, and underpasses that safely bypass highways, interchanges, and short waterways to connect critical segments of the greenway network, with an initial focus on greenway intersections with Newtown Creek, Westchester Creek, the Belt Parkway, Hutchinson River Parkway, Grand Central Parkway, and the Bronx River Parkway.

Map out and publish plans for the entirety of the bike lane network instead of presenting individual projects or segments to help New Yorkers understand the larger vision, reduce the amount of project review time within city agencies, and gather holistic public comments.

Lane Recommendations

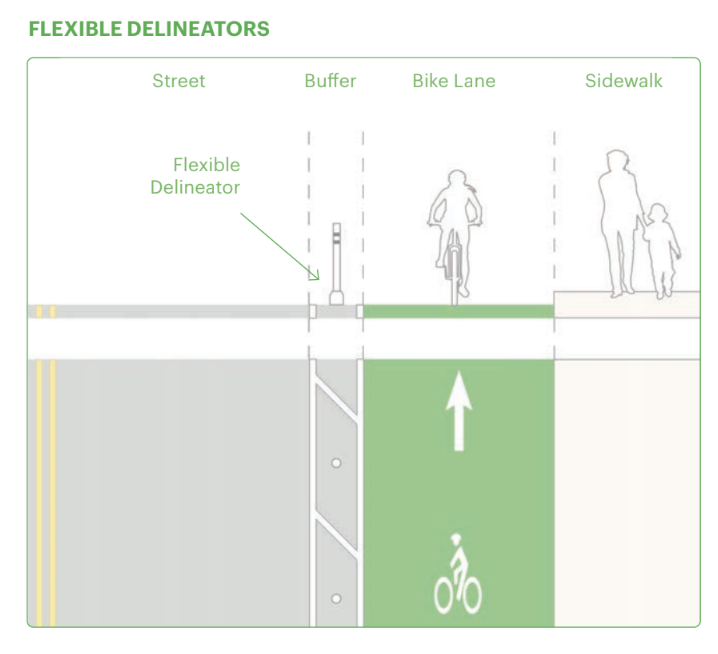

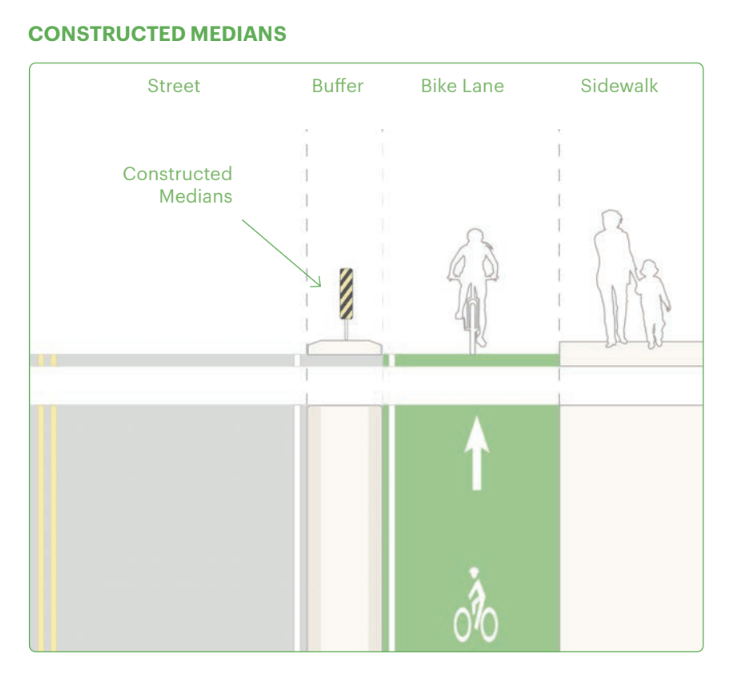

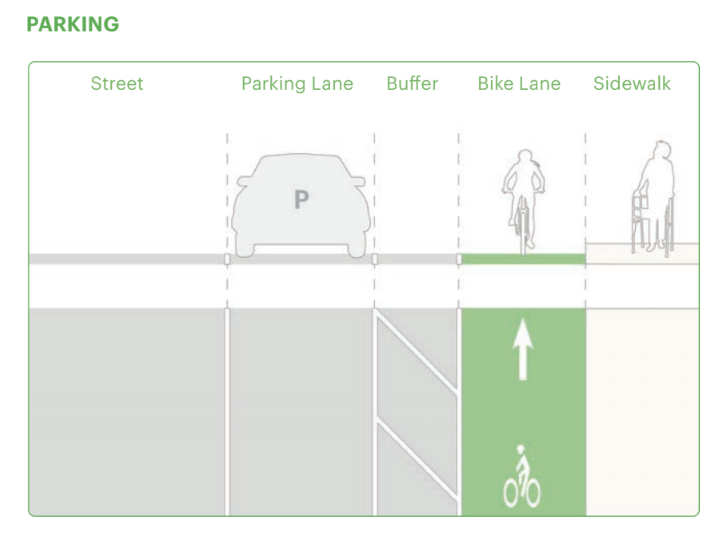

Accelerate the conversion of existing painted bike lanes into protected bike lanes, separated from moving traffic and parking with hardened infrastructure guarding the entirety of the lane.

Standardize wider bike lanes in all neighborhoods with high volumes of bike use, especially those neighborhoods with higher than average e-bike and commercial bike traffic.

Expand the use of bike boulevards and bicycle streets with limited through-traffic.

Image credits: NACTO Urban Bikeway Design Guide

Make the Department of Transportation’s “Better Barriers” pilot program permanent, implementing barriers on existing bike lanes modeled on the most successful pilots of that program and setting this as a standard for all future lanes.

Set a standard that all future bike lanes will be protected from moving traffic and parking with hardened infrastructure and, after passage of a state bill to allow for it, automated enforcement guarding the entire lane.

Where necessary, build paint-only buffered bike lanes, which have been shown to reduce speeding and encourage ridership, in communities where bike lane projects have stalled due to community opposition.

Intersection Recommendations

Daylight all intersections with hardened infrastructure to improve the ability of pedestrians, people on bikes, and drivers to see one another.

Expand protected intersections along existing bike lanes to force drivers to make slow turns through the intersection.

Require all new protected bike lanes to be developed with protected intersections.

Require a separate lane and signal phases for turning cars at high-volume intersections and truck routes where vehicles are required to cross a bike lane.

Continue green roadway markings through the intersection along all green painted bike lanes.

Image credits: NACTO Urban Bikeway Design Guide

Advance Generational Infrastructure Projects That Account for Cycling Growth

Generational infrastructure projects require substantial capital budget allocations over multiple years and can span administrations. These projects provide transformative access to bike infrastructure for current and future generations, but require the foresight to plan for growing populations of people on bikes that might not yet exist. Strong political will is essential to accommodate and encourage growth in cycling, and large-scale capital projects must incorporate future projections for ridership, not just current levels.

Just as major infrastructure investments made in bicycle and pedestrian greenways on the Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens waterfronts and dedicated bike paths on the East River bridges laid the foundation for bike ridership growth in the past decade, major infrastructure investments will form the backbone of a future citywide network.

These investments should include:

Major Arterial Thoroughfares: Modeled on the protected bike lane on Queens Boulevard, transform the entire length of major arterial thoroughfares in every borough with bi-directional curb-protected bike lanes, such as Flatbush Avenue, Atlantic Avenue, Hylan Boulevard, Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard, Broadway, and the Grand Concourse.

Bike Access on All Bridges: Modeled on the protected bike lane on the Brooklyn Bridge, expand bike access to all bridges, including bridges that have no bike access, such as the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge; bridges with bike access that is currently at capacity, such as the Harlem River, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro Bridges; and bridges with unsafe crossings, such as the Bronx River and Newtown Creek crossings. Adding bike access to some bridges is as easy as converting a travel lane, while others require careful planning ahead of once-in-a-generation capital bridge rehabilitation projects.

Great Public Spaces with Bike Access: Modeled on the Allen Street Mall and Broadway between 14th Street and 34th Street, create shared public spaces for people on bikes, people walking, as well as shopping, outdoor dining, and other activities. An example of a prime opportunity for these shared spaces is the Park Avenue Viaduct at Grand Central Terminal, which could create crosstown greenway and lane network connections for people on bikes as well as public space at one of the city’s largest public transportation hubs.

Enforce and Maintain a High-Quality Bike Lane Network

A well-maintained bike lane network is well-paved, clearly marked, free of parked cars and other obstructions, and managed by a fully staffed and funded Department of Transportation. While bike lane network enforcement and maintenance are far less costly and demanding than maintaining a road or transit system, the utility of a bike lane network is still as contingent on its maintenance and enforcement as its safety and connectivity. Both maintenance and enforcement are a matter of capacity.

Capacity Recommendations

Fully fund and staff the Department of Transportation with improved planning and construction capacity.

Develop a combined project design group within the Department of Transportation for both quick-build and capital projects in an effort to foster more ambitious design solutions.

Fully fund and staff the Parks Department maintenance division for bike paths and greenways.

Increase NYPD towing capacity to remove obstacles from bike lanes.

Conduct a citywide assessment of towing needs and capacity, including general tow capacity for passenger vehicles, tow capacity for large obstructions such as dumpsters, buses, and tractor trailers, towing locations, and the legal authority to address hazardous conditions and relocate vehicles out of lanes.

Expand capacity for snow removal, greenery pruning, and pothole filling along the bike network.

Increase the number of bike counters employed citywide and measure bike volumes and ridership, with the goal of using ridership data to improve bike lane maintenance, bike lane width expansions, and bike parking capacity.

Maintenance Recommendations

Dedicate a staff member in the bike division at the Department of Transportation to document, audit, and coordinate bike lane maintenance between the Department of Sanitation, and the New York City, State, and National parks departments, with a focus on snow removal, trash removal, and trimming during growing seasons.

Direct the Department of Transportation to coordinate with the Department of Sanitation to crack down on illegal dumping in bike lanes and greenways while targeting trash pickup and street sweeping schedules to keep lanes clear.

Set clear designations for which agency or department is responsible for maintaining and trimming back greenery along greenways and protected bike lanes, with aggressive schedules that coordinate with growing seasons.

Enforcement Recommendations

Issue a request for proposals for an automated bike lane parking enforcement bus-mounted camera pilot program that automatically tickets drivers who park in the bike lane, as already permitted under law, and pass the related legislation in Albany.

Empower NYPD Traffic Enforcement Agents with bike lane inspection patrols to encourage ticketing, towing, and clearing of bike lane obstructions. Develop a program that gives Traffic Enforcement Agents the opportunity to patrol on bike.

Using automated camera enforcement and NYPD Traffic Enforcement Agents, significantly increase the number of parking tickets issued for obstructing bike lanes.

Facilitate Reliable Bike Access

A bike network is of little use without a bicycle, and the City of New York can facilitate more people riding bikes by ensuring more people have reliable access to a bike. Case in point: New York City’s bike boom began with a bike share program that gave millions of New Yorkers access. A reliable bicycle is affordable, accessible, and safely storable.

Bike Parking & Storage Recommendations

Complete the rollout of the proposed citywide on-street secure bike parking program.

Create secure e-bike charging stations at bike delivery hubs, outside NYCHA buildings, and in neighborhoods with large populations of food delivery workers.

Require all office and residential buildings to permit bikes indoors via elevators. Create a system for lodging and enforcing complaints against non-compliant building owners. Regularly audit New York City’s largest residential and office buildings for compliance.

Increase the number of required secure bike parking spaces in new construction. Create zoning changes or tax incentives so that more new or renovated buildings and businesses have ample bike parking, e-bike charging, or shower facilities for commuters.

Bike Share Recommendations

Expand Citi Bike access citywide with City funding.

Expand low-income Citi Bike access programs, currently serving SNAP recipients and NYCHA residents.

Create a $5 Citi Bike membership for City employees, and New York City public high school and City University of New York (CUNY) students.

Site Citi Bike docks near transit stations in future rollouts and station relocations to make it easier for people to shift from bike to transit to bike.

Affordability Recommendations

Develop a commuter benefits cash-out program so that employees with parking benefits can use those funds to purchase and maintain a bicycle.

Create a subsidy program for purchasing an e-bike and trading in a gas-powered car or moped for an e-bike.

Fully fund bicycle lessons for adults and children, free helmet giveaways, and support for nonprofits and community organizations that encourage active transportation with group rides and hands-on education.

Implement Policies That Encourage People to Ride Bikes

The planning and policies that precede infrastructure and define how infrastructure is used directly affect who feels safe riding a bike in New York City. Simple policy changes can influence bike ridership citywide, often without large budget allocations or planning.

Policy Recommendations

Expand Summer Streets to a weekly event from April to October, modeled on Ciclovía (as well as similar programs in Westchester and Los Angeles), adding mileage each year with a goal of creating a connected car-free cycling space citywide.

Considering that safety is the leading factor keeping people from riding bikes, and that vehicle speeds directly affect the safety of cyclists, implement Sammy’s Law citywide.

Reset traffic signals along major bike routes with a “green wave” signal to reduce stop-and-start bicycling and make bicycling and vehicle flow smoother and safer.

Expand Intelligent Speed Assistance requirements and best-in-class vehicle safety technologies to all vehicles in the City of New York’s fleet, those licensed by the Taxi & Limousine Commission, and any under contract with the City.

To address rising concerns from pedestrians and cyclists about e-bike and moped use, create a system to regulate the food delivery app industry that puts the onus of safety and safe work requirements on app companies. This would allow workers to slow down and do their jobs while prioritizing their safety and the safety of others.

Repeal the new NYPD policy of escalating minor traffic violations by people on bikes to criminal summonses.

Prioritization Recommendations

Considering that safety is the leading factor keeping people from riding bikes, prioritize the construction of bike lanes on streets with high rates of speeding, crash rates, pedestrian and cyclist fatalities, and serious injuries, and in communities with the least access to bike infrastructure relative to ridership.

Map out where bike lanes are needed to encourage cycling rates that better match the city's demographics, prioritizing communities where ridership currently outpaces infrastructure, and where there is identified pent-up demand for the option to ride a bike.

Begin planning and implementing protected bike lanes to connect with future Metro-North stations in the Bronx and Interborough Express stations in Brooklyn and Queens, with “park and ride” secure bike storage.

Coordinate protected bike lanes from critical transit desert neighborhoods to the closest subway stations, and work with the MTA to develop “park and ride” secure bike storage at stations.

Administrative Recommendations

Collect annual demographic data on bike ridership to ensure that the city’s bike-riding population matches the city itself, including race, ethnicity, income, gender, as well as information on family and student cycling.

Reintroduce bike lane construction and connectivity as a metric in the Mayor’s Management Report and expand it so that each borough, council district, and community board is scored separately.

Set a ridership metric for converting existing painted bike lanes into protected bike lanes.

Require the addition of bike lanes for any street redesign that is a mile or longer.

The Present and Future Bike Network: By Borough and in Brief

The Bronx

In the Bronx, the protected bike lane network benefits from an extensive system of large parks with rideable paths and connective greenways. However, the on-street protected bike lane network is more fragmented than any other borough. It generally lacks critically important “spines” — protected bike lanes on major arterials that traverse multiple neighborhoods, as seen in Manhattan, Queens, and Brooklyn. The borough's nonuniform street grid means a few arterials will be especially critical to creating key spines throughout the borough. Furthermore, unlike the other boroughs, the Bronx lacks good connections with Manhattan. The most critical next segments for network connectivity are Harlem River bridge crossings and connecting the bridges to the network on both sides, east/west segments, the Harlem River Greenway, connections across Westchester Creek, and hardening existing bike lanes, such as on the Grand Concourse.

Brooklyn

In Brooklyn, the existing protected bike lane network is more extensive and connected than any other borough outside Manhattan, thanks to an expansive coastal greenway system and significant investment in certain neighborhoods. However, most of this connectivity is centered in Downtown Brooklyn, Williamsburg, and Greenpoint. These neighborhoods were also the first to have bike share access outside Manhattan, boosting local ridership. Otherwise, the network relies on a fragmented greenway along the coast and three mostly disconnected north-south spines at 4th Avenue, Ocean Parkway, and Bedford Avenue. Two of these spines — 4th and Bedford — are incomplete and dead-end on treacherous streets. East-west connectivity is extremely limited, fragmented, and made up almost entirely of unprotected bike lanes. The most critical next segments for network connectivity would be east-west connectivity south of Prospect Park, along with connecting Bed-Stuy and Bushwick to the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridge bike lanes, completing the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, and further extending north-south connections in central Brooklyn and toward East New York.

Manhattan

Manhattan’s protected bike lane network below 60th Street is good, and in some places extensive, but with critical gaps remaining. Because of Manhattan’s unique role among the boroughs as a work, school, transit, and cultural hub, its streets need to be accessible by bike for people all over the city. But today, Upper Manhattan lacks any resemblance to a network, with no east/west connections. The East Side of Manhattan lacks southbound access, putting high volumes on 2nd Avenue. More crosstown lanes would add connections throughout the congestion relief zone, cultural epicenters of the city, and major commuting hubs like Penn Station and Grand Central. The focus should be on widening lanes to accommodate higher volumes and different types of bikes and micromobility devices, especially below 60th, east/west access across Harlem and Inwood to connect the Bronx River bridges to the Hudson River Waterfront Greenway and across Central Park, and a north/south connection north of 110th on the west side of the borough, and an additional southbound route on the east side.

Queens

The Queens protected bike lane network misses the mark on connectivity. Most prominently, the essential interborough connector — the Queensboro Bridge — remains overcrowded and dangerous as plans to open the South Outer Roadway to walking and biking remain stuck in political limbo. Queens Boulevard, which stretches east/west across most of the borough, is a critical single spine with only one major offshoot, Crescent Street. Due to its length and bifurcation of the borough, the Queens Boulevard protected bike lane creates a spine to launch a near borough-wide network. However, the situation is more dire in Eastern Queens, with the waterfront Central Greenway as the only substantial, but disconnected, segment and a more suburban and car-dominant layout than its Western counterpart. The most critical next segment for network connectivity could be creating those north/south segments off Queens Boulevard, creating a second spine off of the Northern Boulevard splinter through the 34th Avenue Open Street past Citi Field and through Flushing, supporting high and growing ridership with a true neighborhood network in Astoria, implementing Destinations Greenways in eastern Queens, and better connectivity with North Brooklyn.

Staten Island

Staten Island's protected bike lane network is essentially non-existent, with only two substantial segments in the entire borough, the New Springville Greenway and the Staten Island Waterfront Greenway, neither of which connects with the other. The most critical segments needed next for a protected bike lane network are in St. George connecting to the Staten Island Ferry, the Verrazzano Bridge, and an east/west connection parallel to the Staten Island Expressway.

Acknowledgments

Transportation Alternatives is grateful to all those who developed Transportation Alternatives’ original Bicycle Blueprint in 1993, as well as the New York City Department of Transportation, Citi Bike, Bike New York, the NYC Greenways Coalition, and the Brooklyn Greenway Initiative for contributing their insight to this 21st-century version.