Open Streets Forever

The Case for Permanent 24/7 Open Streets

Published October 12, 2021

Executive Summary

Open Streets are popular, beloved, effective, and lifesaving. But, new research from Transportation Alternatives (TA) found that the benefits of Open Streets — from reduced traffic violence to accessible public space in the most deprived communities — are lost when subpar infrastructure allows car drivers to dominate that space. Our research also found significant inequities in the planning and operation of the program.

“There aren't many spaces in our community where we can stop and play in a safe place. The Open Street has been offering activities for the whole family every week, along with musical performances and educational resources. The whole community has been enjoying the use of this open space and it has transformed how many of us look at the streets we live on.”

With the help of hundreds of volunteer surveyors (including more than 350 unique participants completing nearly 800 surveys — a force of volunteerism that is a testament to the belovedness of this program) — TA documented conditions on the ground at every Open Street in New York City and analyzed how those results compared to the Open Streets plans listed by the City of New York.

(For the purposes of this report: “listed” Open Streets are those on the New York City Department of Transportation (DOT) website. “Active” Open Streets are those that at least one surveyor said were active — meaning one person observed the barricades in the street at any time during planned operating hours, even just once, and even if other surveyors’ observations disagreed. “Non-operational” Open Streets are those where no surveyors found barricades in the street on any visit. “Walking distance” is living in a census tract that is within a quarter-mile of an Open Street. Surveyors were asked to report results after observing the Open Street for five minutes.)

Key findings include:

Of 274 Open Streets listed by the DOT, only 46 percent, or 126 total Open Streets, were found by surveyors to be active. This is equal to 24.01 miles of Open Streets in operation in 2021. This is around 30 percent of 2020’s total length, less than 0.04 percent of New York City’s 6,300 miles of streets, and well short of the 100 miles promised by Mayor de Blasio.

Just one in five New Yorkers live within walking distance of an active Open Street.

Of all the active Open Streets in operation today, 33.7 percent are in Manhattan, 32.3 percent are in Brooklyn, 25.5 percent are in Queens, 6.3 percent are on Staten Island and only 2.2 percent are in the Bronx.

In the Bronx, 84 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational. In Queens, 69 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational. In Brooklyn, 60 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational. On Staten Island, 44 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational. In Manhattan, 34 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational.

Manhattan residents have access to 1,409 percent more miles of active Open Streets than Bronx residents.

Open Streets in predominantly white neighborhoods were significantly more likely to be car-free. If 75 percent or more of the people living within walking distance of an Open Street were white, it was four times as likely that surveyors found the Open Street to be car-free for the first five minutes they were there than if 75 percent or more of the people living in walking distance were Black.

Despite all this, New York City’s Open Streets are injury-reducing, economy-saving, popular, desired, and truly beloved by New Yorkers. TA found:

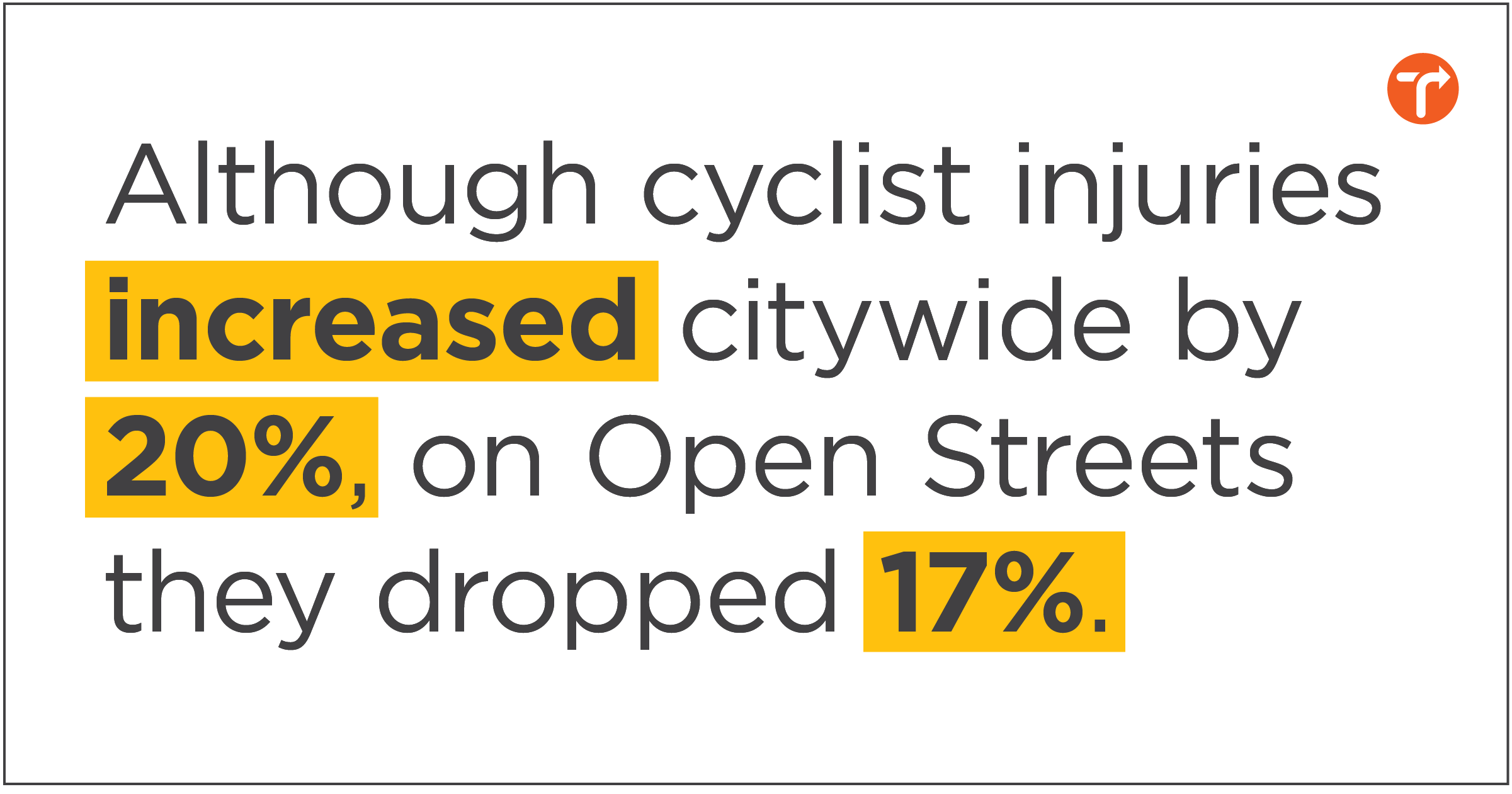

While cyclist injuries increased 20 percent citywide, cyclist injuries decreased 17 percent on Open Streets (between the twelve months before the pandemic and the twelve months since Open Streets were announced).

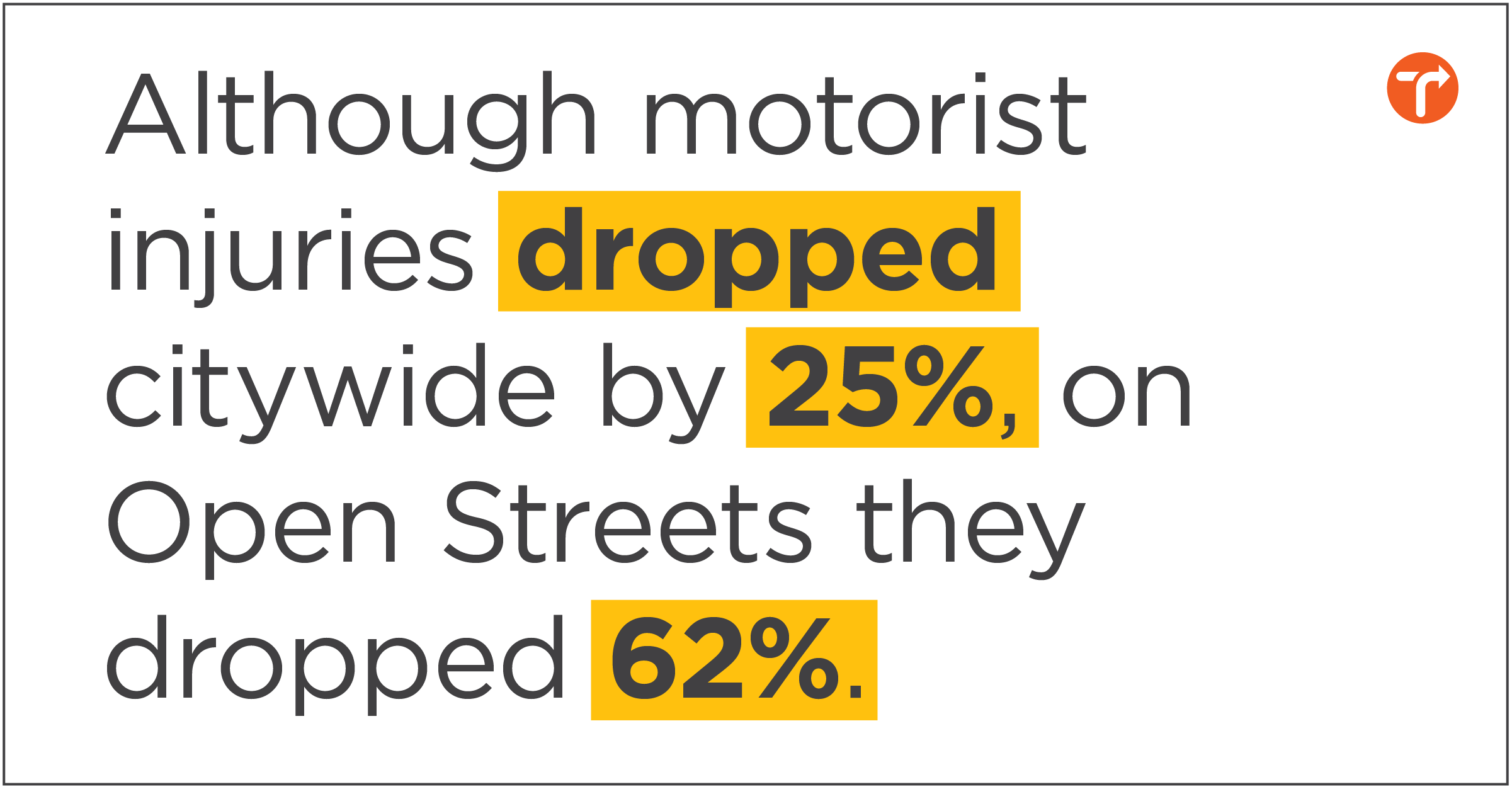

While motorist injuries fell by 25 percent citywide, motorist injuries fell by 50 percent on Open Streets (between the twelve months before the pandemic and the twelve months since Open Streets were announced) — even though no Open Streets operate 24/7.

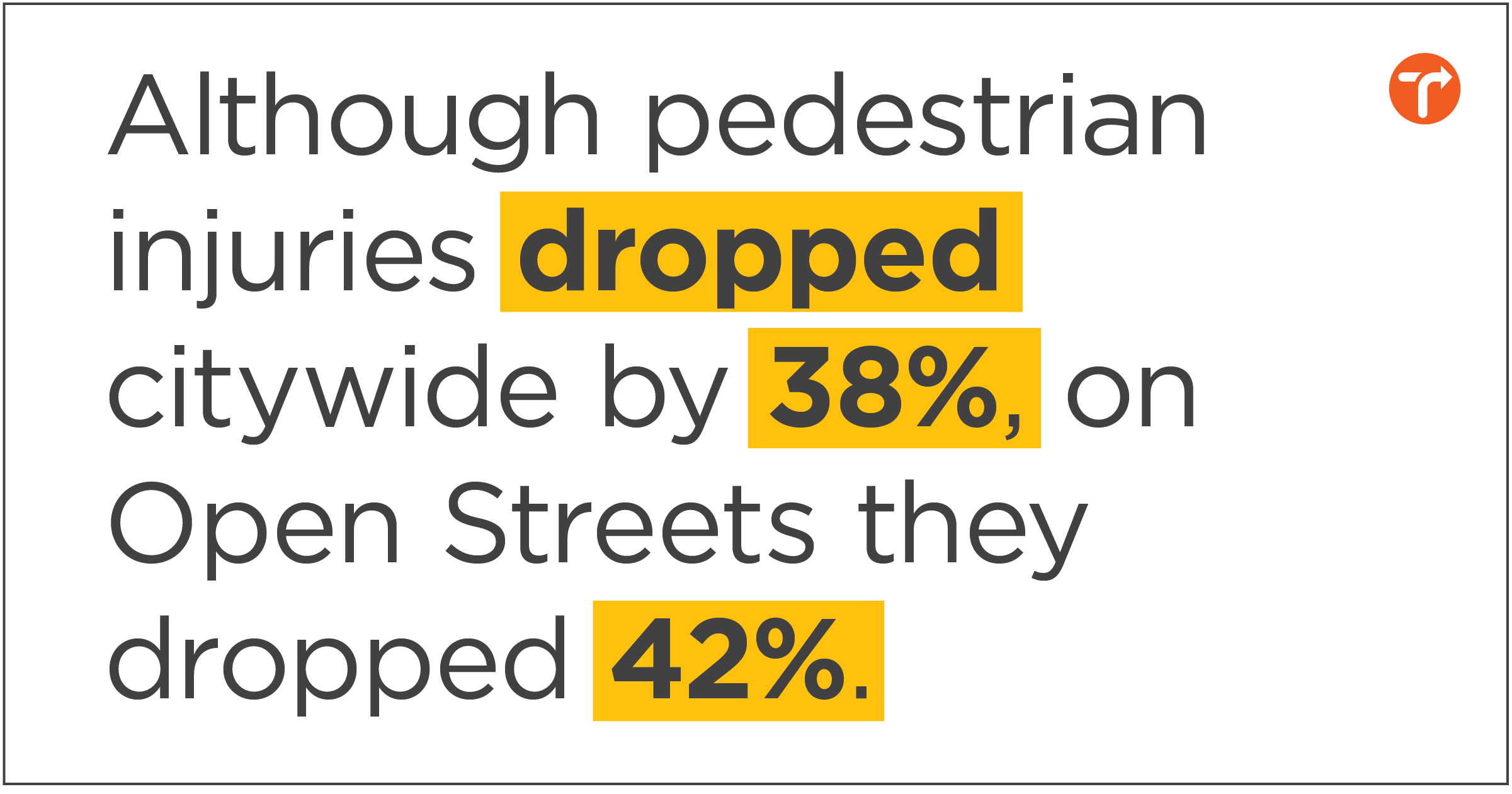

While pedestrian injuries fell 38 percent citywide, pedestrian injuries on Open Streets fell 42 percent (between the twelve months before the pandemic and the twelve months since Open Streets were announced) — even though pedestrian counts skyrocketed on Open Streets.

An estimated 100,000 jobs were saved when around 10,000 New York City dining establishments moved their business onto the streets and sidewalks, occupying fewer than 9,000 of New York City’s more than three million parking spaces.

After the first year of the program, polling by Siena College conducted for TA found that 63 percent of New York City voters support closing streets to cars to open them to people, including 57 percent of car owners. DOT polling found that 81 percent of people surveyed said they wanted Broadway to be a permanent Open Street, and 86 percent felt the same about Open Streets in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn.

Mayor Bill de Blasio promised 100 miles of Open Streets, and that “equity and inclusion will be at the heart of the Open Streets expansion, with underserved neighborhoods getting new opportunities to participate.” By visiting every Open Street in New York City at least once, we found that these promises have not been met. There are also significant disparities between listed Open Streets and active Open Streets, as well as major borough-to-borough, racial, and economic inequities in the quality and quantity of Open Streets.

However, we also found passionate testimonials and deep affection for the program. This tension underwrites this report: Open Streets are amazing and must be better.

Even if New York City met its promise of 100 miles of Open Streets, this would encompass only 1.6 percent of streets returned to people. Looking only at this summer’s active Open Streets, that number falls to less than 0.04 percent of New York City’s streets. In a dense city struggling under concurrent and rising crises of racial injustice, health catastrophe, and environmental collapse — pollution, asthma, traffic violence, and an ongoing airborne pandemic — this is simply not a fair share of space for New Yorkers.

“There were musicians playing, groups of cyclists moving though in an organized fashion, and many local businesses taking advantage of the street...There were many people remarking that the street felt like a block party.”

New York City’s next leaders must turn Open Streets into permanent, 24/7 fixtures of the streetscape, as part of an effort to convert 25 percent of car space into space for people by 2025. Open Streets are an integral part of TA’s NYC 25x25 challenge to New York City’s next leaders. Permanent 24/7 Open Streets — designed to discourage car driving and dramatically limit traffic speeds — will not just improve the quality of each Open Street, but save lives citywide and transform the day-to-day existence of New Yorkers. To create permanent 24/7 Open Streets, the City of New York should narrow the entrance to Open Streets with curb extensions, including chicanes, bus bulbs, and pinch points, using bike parking, bioswales, and street trees and invest in a system of permanent and semi-permanent bollards and barricades that discourage through traffic and lower traffic speeds to five miles per hour. With these simple changes, the City of New York can deliver new open space that will reduce traffic violence, asthma, and pollution while providing flood-mitigating climate resiliency and life-altering access to active living in every neighborhood.

Recommendations in Brief

Transform all Open Streets into permanent 24/7 fixtures of the streetscape, reducing or eliminating on-street parking, and installing a variety of permanent bollards, barriers, and curb extensions to discourage car access and slow driving speeds to five miles per hour.

Lengthen all Open Streets to a minimum half-mile.

“The street was blocked off with metal barricades adorned with a street closed sign. There was a group of children singing and playing, seemingly from a summer camp program. This street seems to be successful because it often has groups that are committed to using the street, which makes everyone respect its open status.”

Conduct an audit of traffic-related harms, including green space distribution, asthma rates, congestion, air quality, heat island effects, and traffic violence. Distribute Open Streets and Open Streets resources based on this audit, locating permanent 24/7 Open Streets to improve air quality, congestion, and access to open space, and to reduce traffic violence, asthma hospitalizations, and speeding.

Provide the resources required for City agencies to be the primary caretaker of Open Streets. Where agency staff is unavailable, create and fund an Open Streets Caretaker program, which pays local businesses, community organizations, and residents to care for Open Streets.

Deliver on the promises of 2020 and 2021 Open Streets legislation, including the immediate opening of 20 DOT-managed permanent 24/7 Open Streets.

Pioneer New York City’s first Low Traffic Neighborhoods, surrounding already low-traffic Open Streets.

Expand the School Streets program to close one street outside every New York City school, providing car-free space for drop-off and pick-up, as well as temperature checks, play, and outdoor learning.

Expand the Open Streets program on special occasions, including Halloween and Air Quality Alert Days, to provide cleaner air and more open space to New Yorkers when and where it is most needed.

Acknowledgments

Transportation Alternatives (TA) is extremely grateful to the many volunteers who devote extraordinary time and energy maintaining and activating New York City’s Open Streets, to the members of the New York City Open Street Coalition that advised on and supported the creation of this report, to the City Council staff that wrote and pushed through Open Street legislation in a pandemic and advocated for the program in their districts, to the DOT staff that developed and executed an innovative new street reclamation program in a pandemic, and most especially to the hundreds of volunteer surveyors who visited every single Open Street in New York City many times over and created the remarkable data pool on which this report is based. Thank you.

“Open Streets are hands down one of the best services provided to New Yorkers.”

Introduction

New York City’s Open Streets have several forebears — from the open markets of the Lower East Side serving shoppers at the turn of the 20th century, to the Play Streets that provided safe space for children to play when cars began to overrun city streets in the 1920s, to the plaza program that pedestrianized Times Square and opened countless other underused city streets to people at the turn of the 21st. It is this history that guided Transportation Alternatives (TA), in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, to help introduce the idea of Open Streets to New York City. Open Streets are an easily implementable way to create car-free spaces to aid New York City’s recovery and allow space for physical distancing.

“It's such a needed addition to our neighborhood and also drives a real sense of community. I saw a lot of parents and families using the Open Street to push baby strollers or let their kids scooter or bike down the street.”

As New York City shut down in the spring of 2020, TA developed and published information about how Open Streets could give critical space to New Yorkers and boost local economies by providing a route to reopening, and organized New Yorkers to move the idea of Open Streets from a pilot project to a permanent feature of our streetscape.

Under public pressure, Mayor Bill de Blasio responded by reluctantly launching a heavily-policed 1.6-mile Open Streets program. TA warned that this half-hearted effort would not succeed: for public space to serve people, it must be accessible to people, and that means it is both within walking distance and not monitored by police officers who make people feel rightly unsafe being outside. We proved right — this minuscule, inaccessible, and heavily-policed Open Streets pilot was poorly attended and quickly discontinued. TA called on the de Blasio administration to not give up but to do better — allocating time and resources to an accessible, safe, citywide Open Streets program.

The New York City Council responded directly to TA’s demand. Following the leadership of Speaker Corey Johnson, Council Member Carlina Rivera, and Transportation Committee Chair Ydanis Rodriguez, the New York City Council introduced a law that would force Mayor de Blasio to open 75 miles of streets for people by closing them to cars. In response, Mayor de Blasio insisted he would open 100 miles of streets to people. This 2020 plan, while the most ambitious Open Streets program in the United States at the time, was flawed in Mayor de Blasio’s implementation. In the spring of 2020, New York City’s Open Streets were slow to roll out, centralized in the wealthiest neighborhoods, too disconnected to serve transportation needs, and “protected” by subpar materials often dismantled by the end of the day.

To shift this course, TA and our partners rolled out the Open Streets Coalition — more than 140 community organizations from across the city united to demand the use of Open Streets to aid New York City’s recovery. For nearly two years, this coalition has met twice a month to tackle ongoing challenges and advocate for improvements to the Open Streets program. In the late spring of 2020, TA and our partners pushed for the ambitious use of Open Streets for transportation, dining, retail, recreation, and public health in an open letter to the mayor. By June 2020, Mayor de Blasio agreed to some of these demands, including launching Open Streets for outdoor dining.

“These kinds of safe spaces are so important, especially in the Bronx, where we lag substantially behind in health outcomes and transportation access.”

In the summer of 2020, TA’s report — The Unrealized Potential of New York City’s Open Streets — analyzed Open Streets’ locations and resources and found the program to be a good idea poorly executed. TA’s critique led to an accelerated rollout of Open Streets in the most needful places, stronger materials protecting pop-up bike lanes, and eventually a mayoral promise to make Open Streets for outdoor dining permanent.

When the program relaunched in the spring of 2021, New Yorkers flocked to the streets after a long winter inside, taking advantage of these new open spaces, often closer to where they lived than accessible parkland. In many places, volunteers wholly carried the management of their local Open Streets: setting up barricades daily, planning programming, hand-painting signage, and more. The growth of Open Restaurants provided an economic lifeline to some 10,000 dining establishments in New York City, and on the few Open Restaurant streets, car-free places with ample dining options became outdoor evening community centers, hosting live music and picnickers in their medians. From early morning yoga classes to evening nightcaps, Open Streets have become beloved parallel parks and local economic anchors in one of the hardest years in our city’s history.

To assess the Open Streets program, now in its second year, TA stepped up our data collection and listened to the volunteers who have been operating Open Streets around the city and the small business owners who have been able to reopen thanks to accessible car-free space in the streets outside their businesses. This report contains the results of that investigation and our recommendations for the future of this beloved New York City program.

“People feel safe there...Families with strollers, with little kids who can run around, kids on scooters. It really lets everyone breathe. We need more of this!”

Key Findings

This summer, TA built a surveying system where anyone could report on-the-ground conditions at one of New York City’s 274 listed Open Streets. With the help of hundreds of volunteers, that effort visited every single Open Street in New York City, collecting close to 800 responses from New Yorkers in all five boroughs.

For the purposes of this report: TA used an extremely generous definition to decide whether or not an Open Street was “active.” An Open Street was considered active if a single surveyor observed the barricades in the street at any time during listed operating hours, even just once, and even if other surveyors’ observations disagreed. “Non-operational” Open Streets are those where no surveyors found barricades in the street on any visit. “Walking distance” is living in a census tract that is within a quarter-mile of an Open Street.

Surveyors observed an Open Street during listed operating hours for five minutes and reported in that time on:

The type of barricades protecting (or failing to protect) the Open Street

The status and location of those barricades in (or off) the street

How many people used the Open Street

The activities that people in the street (not on the sidewalk) were partaking in

If (and how many) incursions by cars occurred on the Open Street

And how inviting they felt the space was and what they would rate the space on a scale of one to 10.

Based on these surveys, as well as an analysis of information published by the New York City Department of Transportation (DOT) on the location and length of Open Streets, and U.S. Census data, TA found:

Most New Yorkers cannot access Open Streets

Most New Yorkers do not have access to an active Open Street. Just one in five New Yorkers live within walking distance of an active Open Street. Active Open Streets make up less than 0.04 percent of New York City’s street mileage.

However, on average, 30,977 New Yorkers live within walking distance of a listed Open Street. By improving conditions at Open Streets so that all of them are active, the City of New York has the potential to impact a small town's worth of people at every single listed Open Street location.

TA hoped that the Open Streets program would correct existing inequities in access to parkland and greenspace. Unfortunately, this has not occurred: There are zero active Open Streets in any of the six community board districts that have the fewest residents living within walking distance of a park. (Those are: Queens districts 10 and 13; Bronx district 10; Brooklyn districts 14 and 17, and Staten Island district 3.) However, the potential of Open Streets remains. Even if open space and parkland are inequitably distributed today, every neighborhood is crisscrossed with streets, which, if reclaimed, can become open space. Today, over three-quarters of the space on our streets is dedicated to storing and moving vehicles. Reclaiming just a fraction of that space for people, as is laid out in TA’s NYC 25x25 challenge, by equitably distributing Open Streets, would allow us, with razor-like precision, to eliminate most if not all inequities in public space.

“The worst part is getting there. My mother is wheelchair-bound and it takes us 10-15 minutes to get there, too often on cracked and narrow sidewalks...Before we discovered this gem we had limited things we could do. This has completely changed our relationship and I now see her more often because we both enjoy this program so much.”

Access to open space has been shown to improve mental health outcomes in adults and children and decrease unemployment. Converting car space into space for people has been shown to reduce carbon emissions and parking demand. Cities that reduce space for cars also see reductions in the heat island effect, particulate matter in the air, rates of asthma, preterm birth, heart disease, depression, and other public health challenges, and increases in quality of life, life expectancy, air and water quality, and rates of physical activity. For example, converting car space into pedestrian plazas in Times Square reduced nearby nitrogen oxide pollution by 63 percent and nitrogen dioxide pollution by 41 percent. Both pollutants lead to direct health consequences in humans, including cardiovascular and respiratory health diseases.

The majority of DOT-listed Open Streets were not active

Of 274 Open Streets listed by the DOT, only 46 percent, or 126 total Open Streets, were found by surveyors to be active.

Whether an Open Street was active or non-operational had a significant effect on how many cars drove through the space. If an Open Street was non-operational, on average, surveyors found more than 10 cars drove down the Open Street in the first five minutes. If an Open Street was active, surveyors found that, on average, less than three cars drove down an active Open Street in the first five minutes.

The disparity between listed and non-operational Open Streets is a major problem. Residents see listed but non-operational Open Streets as a broken promise and an additional insult, especially in places already at a significant disadvantage for greenspace and traffic safety infrastructure. Further, non-operational Open Streets are still listed on Google Maps as Open Streets; when drivers drive down these barricade-less streets, it sends a message that they are free to drive down all Open Streets. And the failure of the City of New York to even know which Open Streets are active and which are non-operational means that city officials are unaware which Open Streets need more resources and assistance.

“I have lived on this street for fifty years, but only noticed the caryatids today. I had never had a chance to stand where one can appreciate the architecture.”

Open Streets prevent injuries

Looking at the most popular and visited Open Streets, as measured by the number of surveyors, there was a dramatic reduction in injuries compared to the rest of the city.

TA compared the number of injuries sustained from traffic violence in the 12 months preceding COVID-19 versus the 12 months since the Open Street program was launched last summer, looking at injury rates at all days and times in total — including when Open Streets were closed. While cyclist injuries citywide increased 20 percent in that period, on Open Streets, cyclist injuries fell 17 percent. While pedestrian injuries fell 38 percent citywide in that period, pedestrian injuries on Open Streets fell 42 percent — even though pedestrian counts skyrocketed on Open Streets. Motorist injuries fell by 25 percent citywide in that period but fell 50 percent on Open Streets. This was true even though none of these Open Streets were open overnight, and even though these Open Streets include intersections where cars are always allowed.

This evidence emphasizes the importance of Open Streets. In 2021, the number of people killed in traffic crashes is on track to rise for the third year in a row, a first for New York City since 1990. The last 12 months have been the deadliest since Mayor de Blasio took office. Around 170 people are injured in traffic crashes every day, some 62,000 a year. Traffic violence costs New York City $4.29 billion a year.

“The 34th Ave Open Street has been a lifeline ever since it was established. I use it every day, and it has changed interactions in my neighborhood.”

Children are especially at risk and as a result, especially stand to benefit from Open Streets. Being struck by a car is the leading cause of injury-related death for New York City children under 14, a population that includes some 1.5 million young New Yorkers. These numbers could plummet if every school had an Open Street outside. Case in point: The Safe Routes to Schools program, which converted car space at 124 high-risk intersections near schools in New York City into daylighting, sidewalk widening, and pedestrian safety islands, brought a 44 percent decrease in injuries for school-age children at those intersections, along with an 11 percent increase in students walking or biking to school.

Longer Open Streets work better, but Open Streets are getting shorter

The majority of Open Streets are shorter than last year. In 2021, surveyors found only 24.01 miles of Open Streets actually in operation, or only 30 percent of last year's total length, or 24 percent of the 100-mile goal set by Mayor Bill de Blasio.

In 2020, half of listed Open Streets were 0.16 miles or shorter. In 2021, half of active Open Streets were shorter than 0.11 miles. (This “shortening” of Open Street was true even though, in 2021, our analysis combined adjacent Open Streets, which we did not do last year.)

“Open Streets has given me and my husband the opportunity to perform our music live for the first time since COVID hit. It was an incredible experience that wouldn't be possible otherwise.”

This is especially unfortunate because New Yorkers prefer longer Open Streets. Surveyors ranked Open Streets higher when Open Streets were longer. If an Open Street was under a half-mile long, it was rated on average 6.6 out of 10. But if an Open Street was more than a half-mile long, it was rated on average 9.1 out of 10.

Making driving difficult makes Open Streets work better

Surveyors observed that when it was difficult to drive down an Open Street, fewer cars intruded on the space. The fewest cars drove down Open Streets where barricades needed to be moved for a driver to proceed down the street. The largest number of cars drove down Open Streets with no barricades in the street. Barricades that were present, but arranged in a way that allowed drivers to travel down the street without those barricades being moved, acted as a minor discouragement from encroaching on the streets.

Of all the Open Streets where surveyors found zero barriers in the street, surveyors also found that in the first five minutes:

98 percent had at least one car drive down the street

90 percent had at least two cars drive down the street

On average, more than 10 cars drove down the street

Of all the Open Streets where surveyors found that barriers were present, but cars could drive around them, surveyors also found that in the first five minutes:

81 percent had at least one car drive down the street

64 percent had at least two cars drive down the street

On average, nearly five cars drove down the street

Of all the Open Streets where surveyors found barricades needed to be moved for drivers to proceed down the street, surveyors also found that in the first five minutes:

70 percent had zero cars drive down the street

19 percent had just one car drive down the street

On average, one car drove down the street

“I had dinner outside at a restaurant with friends. Our three-year-old children played on the median while we ate and socialized. It was one of the most relaxing social things that I have done since my child was born, because the kids could play freely while the adults socialized and ate.”

On average, five times as many cars intruded on Open Streets where drivers could drive around barricades, as compared to streets where barricades needed to be moved for drivers to proceed. Open Streets with no barricades had on average 10 times as many cars driving down them as streets with barricades that blocked the street from cars.

Better barricades meant more physical activity

Open Streets with no barricades were more likely to have no people — more than half of the Open Streets with zero barricades were also devoid of non-driving activity. The opposite was true on streets with effective barricades. On streets that were completely barricaded or where barricades needed to be moved for drivers to proceed, 95 percent of surveyors found activity on the Open Street — people socializing, eating, biking, walking, or running. On Open Streets with zero barricades, surveyors found people socializing just six percent of the time and eating less than five percent of the time. On these unbarricaded Open Streets, 63 percent of surveyors saw no activity at all, and of the remaining 37 percent that did observe activity, the majority just saw people biking through.

On Open Streets with barricades that could not be driven around, surveyors were five times more likely to find people socializing, biking, walking, or running than on an Open Street with zero barricades or barricades that people could drive around.

It is also important to note that while fewer cars drove down Open Streets where barricades needed to be moved for drivers to proceed down the street, and those Open Streets were higher rated and more active, not all drivers are physically able to exit their vehicles to move barricades. This is one of many reasons for the City of New York to create 24/7 Open Streets that use filtered permeability to block all car traffic, or traffic calming infrastructure to discourage driving and slow any vehicle traffic to five miles per hour.

Protecting Open Streets in a way that makes people feel secure can yield significant public health benefits, such as making exercise more accessible and providing space for children to play. New York City ranks 48th among the largest U.S. cities for playgrounds per 10,000 children, and today, there are only eight playgrounds for every 10,000 children in Brooklyn, about half as many as Manhattan, and some Community Districts in Brooklyn and Queens have as few as two playgrounds for every 10,000 children.

“Tonight there is a threat of thunderstorms any minute, and still in a one-minute period when I rested on the 34th Avenue median, 17 people used that one block.”

Streets with fewer cars are also correlated with better social relationships. In New York City, people who live on high-car-traffic streets have fewer relationships with their neighbors and spend less time walking, shopping, and playing with their children than people who live on low-car-traffic streets. Researchers have found that converting a residential street in a low-income neighborhood to a street that prioritizes walking and biking resulted in five times as many neighbor interactions, twice as many children playing, and twice as much time spent playing.

The most beloved Open Streets had the fewest cars

In the survey data, there was a direct relationship between the number of cars that drove down an Open Street during the first five minutes of a surveyor’s visit, and how surveyors rated that Open Street. New Yorkers rated the Open Streets with the fewest incursions by cars the highest.

On average, if zero cars drove down an Open Street in five minutes, surveyors rated that Open Street as 8.3 out of 10. If one car drove down an Open Street, the average rating fell to 7.1 out of 10. However, the average rating of an Open Street falls to 4.3 out of 10 after two or more car incursions.

More than 10 cars driving down an Open Street in five minutes is enough to render the space wholly uninviting. When 11 to 20 cars entered an Open Street in five minutes, surveyors rated it an average of 1.9 out of 10. When 20 or more cars entered the space in five minutes, the average score fell to 1.4 out of 10.

“It's heavily used all times of the day. It would be terrible if it were ever reopened to cars.”

There are very practical reasons why people rated the Open Streets with fewer cars higher: Car-free space is proven to make people happy. Researchers in St. Louis found that car-free Open Streets engendered feelings of optimism in more than nine out of 10 people — noting that the Open Street made the city more welcoming, strengthened the community, and made them feel safer and more positive about the city.

Better barricaded Open Streets were rated higher

Surveyors found a wide variety of barricades protecting Open Streets. More than half were metal barricades and more than a quarter were using multiple types. Around 10 percent were NYPD wooden sawhorses, and only four percent used high-visibility barricades placed by the DOT. However, the barricade type did not have any statistically significant effect on how an Open Street was rated. Barricade placement, on the other hand, had a significant effect.

“I am a regular morning user of Open Streets, which seems to be dominated by people getting in their exercise. I notice a lot of women use the 34th Avenue Open Street to jog and walk in the mornings. I am so happy there is a space that women feel safe using to exercise.”

When barricades were placed in such a way that someone needed to move them for a driver to be able to proceed down the street, the Open Street was rated, on average, an 8.4 out of 10. When barricades were placed with enough room for cars to drive around them, the Open Street was rated, on average, 6.4 out of 10. When barricades were on the side of the road, either on the sidewalk or next to the curb, the average rating fell to three out of 10, and when barricades were absent or destroyed, the average rating of the Open Street was 1.9 out of 10.

While a better barricaded Open Street was higher rated, this barricading can also go too far. When an Open Street was barricaded to such a degree that neither cars nor cyclists could get through, the average rating of the Open Street remained high at 8.1 out of 10, but fell a few tenths of a percentage point from the highest-rated Open Streets — those barricaded to prevent car but not bike access — at 8.4 out of 10.

In general, better barricades meant a more effective and utilized Open Street. An Open Street with no barricades was rated, on average, more than four times lower than an Open Street with effective barricades.

The lowest rated Open Streets are in low-income, Black, and Latino neighborhoods

In his State of the City address in late January, Mayor Bill de Blasio promised that “equity and inclusion will be at the heart of the Open Streets expansion, with underserved neighborhoods getting new opportunities to participate.” This promise has not been met.

Major disparities are revealed when the location of Open Streets is compared by race and income. Open Streets in neighborhoods that are 75 percent or more white were rated higher, on average, than Open Streets in supermajority Black, Latino, and low-income neighborhoods.

Citywide, surveyors ranked listed Open Streets an average of 4.25 out of 10. The average rating of Open Streets rose higher than the citywide average if more than three-quarters of the population within walking distance was white, to 5.27 out of 10. But the average rating of Open Streets fell below the citywide average if more than three-quarters of the population within walking distance was Black, to 2.49 out of 10.

These ratings directly correlate with the rate at which some Open Streets are invaded by cars. More cars drive through Open Streets in Black neighborhoods than in white neighborhoods. If a supermajority of the people living within walking distance of an Open Street were white, it was four times as likely that surveyors found the Open Street to be car-free for the first five minutes they were there than if a majority of the people living in walking distance were Black.

Black and Latino New Yorkers were also significantly more likely to live near a low-rated Open Street, and white and non-Latino New Yorkers were significantly more likely to live near a high-rated Open Street. Low scoring Open Streets correspond directly with missing barricades, more cars, and fewer people observed.

White New Yorkers were more than twice as likely to live near a high-rated Open Street than a low-rated one, whereas Latino New Yorkers were more than 1.7 times and Black New Yorkers two times as likely to live near a low-rated Open Street than a high-rated one. Although Black New Yorkers make up 22 percent of New York City’s population, only 11 percent of Black New Yorkers live within walking distance of the highest-rated Open Streets.

“It is the street of choice for me to take on the way back from work. It feels safe and peaceful to see people walking and dining, similar to being at a resort.”

A similar pattern repeats based on income. Households with an income under $50,000 are significantly more likely to live near a low-rated Open Street while households with an income over $100,000 are significantly more likely to live near a high-rated Open Street. Households with an income of $200,000 or more were more than twice as likely to live within walking distance of a high-rated Open Street than a low-rated one. Every income bracket below $75,000 was more likely to live within walking distance of a low-rated Open Street than a high-rated one. Additionally, any listed Open Street — whether or not surveyors found the Open Streets to be active — was more likely to be in a wealthier neighborhood, meaning that it would not be enough to simply reactivate non-operational Open Streets to reach parity. Making Open Streets fair would require a significant expansion in low-income, Black, and Latino neighborhoods.

These inequities are a significant problem because they both fail to correct and serve to exacerbate existing disparities in public health and environmental outcomes. For example, car-free spaces reduce urban heat island effects and car-filled spaces exacerbate them. Black, Latino, and low-income neighborhoods already bear the brunt of urban heat. Black New Yorkers are twice as likely to die from heat exposure as white New Yorkers. Exhaust from cars makes heat waves much, much worse. And green space counters that effect. Even just using Open Streets to enlarge tree beds can provide more space for trees to grow, a higher likelihood those trees will survive, and a greater cooling canopy over those neighborhoods.

Borough-to-borough, Open Streets are unequal in number, length, and operation

The City of New York’s listed plan for the distribution of Open Streets was inequitable. In practice, these Open Streets were even less fair.

The City of New York planned and listed the following number of Open Streets per borough:

102 Open Streets in Manhattan

90 Open Streets in Brooklyn

42 Open Streets in Queens

31 Open Streets in the Bronx

Nine Open Streets on Staten Island

This means that the City of New York planned for Manhattan residents to have access to 236 percent more Open Streets than Bronx residents and 1,056 percent more Open Streets than Staten Island residents. And all this is despite the Bronx having New York City’s highest asthma rates and Staten Island having the least access to biking infrastructures.

TA examined whether these listed Open Streets were active and found similar disparities. On average, surveyors found that:

In the Bronx, 84 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational

In Queens, 69 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational

In Brooklyn, 60 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational

On Staten Island, 44 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational

In Manhattan, 34 percent of listed Open Streets were non-operational

Even though Brooklyn and Manhattan are home to less than half of New York City’s population, two-thirds of active Open Streets are located in these boroughs. Of all the active Open Street miles in operation today:

33.6 percent are in Manhattan

32.3 percent are in Brooklyn

25.5 percent are in Queens

6.3 percent are on Staten Island

2.2 percent are in the Bronx

Looking at the total mileage of the Open Streets makes the disparity starker. Of all the active Open Streets miles in operation today:

8.06 miles are in Manhattan

7.7 miles are in Brooklyn

6.1 miles are in Queens

1.5 miles are on Staten Island

0.53 miles are in the Bronx

The Bronx did not just have the fewest miles of listed Open Streets and the fewest miles of active Open Streets — those Open Streets, along with those in Manhattan, were also the shortest in the city on average. Looking only at active Open Streets, on average, Open Streets shorter than 0.25 miles made up:

91 percent of Open Streets in Manhattan

80 percent of Open Streets in the Bronx

67 percent of Open Streets in Brooklyn

60 percent of Open Streets on Staten Island

46 percent of Open Streets in Queens

Looking only at active Open Streets, on average, Open Streets shorter than 0.1 miles made up:

60 percent of Open Streets in the Bronx

59 percent of Open Streets in Manhattan

40 percent of Open Streets on Staten Island

38 percent of Open Streets in Queens

33 percent of Open Streets in Brooklyn

“Lots of people are hanging out, chatting, and eating snacks from the cafe. Kids having fun with bubbles, hoola hoops, and paint.”

And the length of Open Streets matters. Across boroughs, surveyors rated longer Open Streets higher. If an Open Street was under a half-mile long, surveyors rated it, on average, a 6.6 out of 10. If an Open Street was over a half-mile long, surveyors rated it, on average, a 9.1 out of 10. The average length of Open Streets that surveyors scored more than nine out of 10 was 60 percent longer than Open Streets that scored under 2.5 out of 10.

Open Streets in the Bronx are least likely to be protected by barricades

People feel that Open Streets are more inviting when cars do not intrude on the Open Street and when barricades protect the Open Street. Despite this, major inequities exist in how protected from cars Open Streets are.

Surveyors found that barricades were present and in the street on every visit:

52 percent of Open Streets in Manhattan

44 percent of Open Streets on Staten Island

29 percent of Open Streets in Queens

22 percent of Open Streets in Brooklyn

Less than 10 percent of Open Streets in the Bronx

People visiting an Open Street in Manhattan had a more than five times higher likelihood of enjoying a car-free Open Street than people in the Bronx. The median number of cars that intruded on an Open Street in the first five minutes that a surveyor was present was 2.5 in Manhattan, three on Staten Island, and five each in Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx.

Open Streets in the Bronx are the lowest-rated in the city

These inequities were reflected in surveyors’ rating of the quality of Open Streets. Surveyors rated Open Streets, on average, lowest in the boroughs where Open Streets were shortest, unbarricaded, least well maintained by the City of New York.

While the average rating given by surveyors to all Open Streets citywide was 4.3 out of 10, only Queens and Manhattan Open Streets, on average, bested this citywide average. Surveyors rated listed Open Streets, on average:

5 out of 10 in Manhattan

4.5 out of 10 in Queens

4.2 out of 10 on Staten Island

4.1 out of 10 in Brooklyn

2 out of 10 in the Bronx

The above ratings include all Open Streets, active and non-operational. Because the Bronx was home to significantly more non-operational Open Streets than any other borough, and because non-operational Open Streets tended to be rated very poorly by surveyors, TA also calculated average Open Streets ratings limited to only active Open Streets. The disparity for the Bronx remained, and Staten Island was added to the list of Open Streets with lower than average ratings.

Looking only at active Open Streets, the citywide average rating by surveyors rose to 6.7 out of 10. Surveyors rated active Open Streets, on average:

7.3 out of 10 in Queens

7.1 out of 10 in Brooklyn

6.7 out of 10 on Staten Island

6.5 out of 10 in Manhattan

5.7 out of 10 in the Bronx

“Completely changes the neighbourhood for the better. This should be made permanent.”

While this active-only rating improves the rating of Open Streets in the Bronx significantly, even when barriers are present, Bronx Open Streets are rated lower than average. Staten Island’s Open Streets’ rating did not change whether considering all Open Streets or only active ones, assumedly because there are so few Open Streets on Staten Island that there are not a significant number of non-operational Open Streets to affect the score.

Despite All This, Open Streets Are Effective, Desired, and Beloved

Despite issues in planning and execution, New Yorkers believe in and desire Open Streets, and adore the active and protected ones to which they have access. From the program’s launch, a remarkable community of volunteers sprang into action across the city, setting up and dismantling barricades daily, hand-painting their barricades, planning programming, cleaning up litter, and becoming street ambassadors and one-block mayors. And their efforts, combined with a small budget from the City of New York and official barricades, have had a transformative effect on many New Yorkers’ lives.

Consider the accounts from surveyors describing their visit to New York City’s Open Streets (which are also dispersed throughout this report):

“I love Open Streets. It makes my soul smile. I feel like I'm part of the community.”

“It's so invigorating to see people strolling and looking around in our neighborhood, rather than just passing through. The Open Streets movement promotes truly experiencing that "NYC-is-all-about-the-people" feeling.”

“I honestly cannot express how much of an impact the open streets have had on my family. They act as a safe place to be outdoors at a time when we are still worried about spending a lot of time indoors. We see friends we hadn't seen during quarantines, we go on long walks and bike rides that before would have been less welcoming, and we've watched kids in our neighborhood use the spaces as they learn to ride bikes, roller skate, and grow while the community watches. It's magical.”

“Open Streets in the Bronx are few and far between currently, but those that exist are peaceful and joyful spaces filled with children and adults enjoying the public way free from the stress of everyday life. These kinds of safe spaces are so important, especially in the Bronx, where we lag substantially behind in health outcomes and transportation access. The successful Open Streets here demonstrate to the community that they can and should feel empowered to reclaim the public realm for activities that nourish the people.”

“I had to pull my kids away last weekend when it was time to leave at Stapleton Saturdays. This neighborhood needs more playgrounds, so Open Streets has been great; I don't even need to drive to bring my kids out.”

The data is as clear as the anecdotes: When Open Streets barricades are present and cars are not, then Open Streets work — reducing traffic violence, cleaning the air, encouraging activity, and making people happy. Open Streets also have the potential to make the inaccessible, accessible. Consider this account:

“The worst part is getting there. My mother is wheelchair-bound and it takes us 10-15 minutes to get there, too often on cracked and narrow sidewalks. Before we discovered this gem we had limited things we could do. This has completely changed our relationship and I now see her more often because we both enjoy this program so much.”

New York City sidewalks are narrow and curb cuts are often absent, but an Open Street, protected by barricades and free of cars, makes space for people to get around on foot, on a bike, using a wheelchair, and with a wealth of other mobility devices. Open Streets also have the potential to serve as a community lifeline. Consider this account:

“As an older person living alone I thought of this experience as an extended family. Please continue this open street. I am sure I am not the only one who enjoys it and looks at it as a family gathering place.”

In the early 2000s, when TA first replicated Donald Appleyard’s classic study of how car traffic affects human relationships, there was ample evidence that New Yorkers who live on low-traffic streets have more social relationships with their neighbors. A protected car-free Open Street multiplies this effect. But the evidence of Open Streets’ popularity is more than anecdotal. Nearly half of New York City schools applied for Outdoor Learning space. Some 100,000 jobs were saved when around 10,000 New York City dining establishments moved their business into the streets.

The Open Streets program is so popular and beloved that New Yorkers dug into their own pockets to support it, on multiple GoFundMe pages. But, despite the ways that these efforts demonstrate New Yorkers’ passion for Open Streets, ad-hoc fundraising also reflects the same disparities in how the City of New York distributes Open Streets resources. Case in point: less wealthy, less white areas, such as Sunset Park, Brooklyn, struggle with such fundraising while more wealthy, more white areas like Park Slope, Brooklyn, excel.

Even after only the first year of the program, polling by Siena College conducted for TA found that 63 percent of New York City voters support closing streets to cars to open them to people. Every age group, income level, and racial/ethnic group showed a clear majority of support, and some groups endorsed Open Streets at an especially high rate: 76 percent of 18 to 34 years olds, and 75 percent of Latino voters want public open access to streets for people, not cars. Non-car-owning households enthusiastically support Open Streets (74 percent) — and so do a majority (57 percent) of car-owning households.

Polling by the DOT found that 81 percent of people surveyed said they wanted Broadway to be a permanent Open Street, closed to car traffic year-round and that 88 percent of those who live or work in the neighborhood use the on-street car-free spaces at least once a week. The benefit was attractive enough to inspire New Yorkers to do something that they rarely do — go out of the way: Of the respondents, 67 percent altered their regular routes to use the Open Streets on Broadway. Other DOT polling in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, where the popular Vanderbilt Avenue and Underhill Avenue Open Streets are located, found that 86 percent of respondents wanted the programs to be permanent. Only seven percent of respondents said that they wanted the program canceled.

And a poll by Data for Progress, conducted for Streetsblog, echoed these findings citywide. Sixty-seven percent of respondents to that poll agreed: the City of New York was right to close streets to cars and open them to people and restaurants. Those results held across economic and racial lines.

Conclusion

Open Streets were introduced to New Yorkers as an emergency initiative during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the 18 months since the program’s introduction, this simple idea has been transformational for New York City and an integral tool for our city’s recovery. Most New Yorkers now believe that streets once reserved for car traffic should be public spaces that serve the public good. Open Streets are beloved, integral, and will remain a critical asset for New Yorkers once the pandemic is over.

However, many of the problems that TA identified in the planning and execution of the program can be traced back to these emergency origins. Open Streets were developed as a temporary program and are still organized as a temporary program, without significant resources or permanent infrastructure.

Further, an Open Street can only do so much. The problems with the Open Streets program are complicated and inseparable from issues of inequity in planning and resource allocation that already plague New York City and our streets’ infrastructure.

“As an older person living alone I thought of this experience as an extended family...Please continue this open street. I am sure I am not the only one who enjoys it and looks at it as a family gathering place.”

For Open Streets to be equitable, the planning and execution of Open Streets need to address and respond to existing disparities. Open Street resources should not be distributed equally across the City of New York, but in response to need and to reduce harm. These are requirements of legislation passed by the New York City Council which have remained unfulfilled. The communities where streets are the most dangerous, parkland the most scarce, and asthma most common, are the communities that need the most investment in their Open Streets. Part of this investment should be in City staff so that communities need not rely on volunteers to manage Open Streets. While in some neighborhoods, these remarkably dedicated teams and individuals are the lifeblood of their local Open Street, relying on volunteers sets up a natural inequity between neighborhoods that are time-poor and those that are time-rich.

While this report shares detailed recommendations, there is also one across-the-board solution to many of the raised issues: Make New York City’s Open Streets permanent 24/7 fixtures of the streetscape — where streets are given back to people by significantly limiting parking and driving using traffic calming infrastructure that discourages driving, controls traffic speeds, and invites more New Yorkers out onto our streets. This will not just improve the quality of Open Streets, but save lives and transform the day-to-day existence of New Yorkers.

Recommendations

Open Streets should be made permanent, 24/7 car-free fixtures of the streetscape, and the City of New York should fund the expansion of the program with necessary infrastructure, distributed based on need and the mitigation of traffic-related harm. This should be part of a citywide effort to convert 25 percent of current car space into space for people by 2025. Transportation Alternatives’ 25x25 challenge to New York City’s next leaders lays out a plan for these transformative changes to the streetscape, including a permanent Open Streets program.

What follows are TA’s recommendations in line with that goal.

Permanent 24/7 Open Streets

Open Streets are a critical tool for reclaiming streets from cars and returning them to people. The City of New York should immediately make every Open Street in New York City permanent, 24/7, open space which is made predominantly or entirely car-free by using durable infrastructure to limit and discourage car-access, and where car-access is permitted, to reduce vehicle speeds to five miles per hour.

By narrowing the entrances to Open Streets — using curb extensions and a system of substantial and semi-permanent bollards and barricades — the City of New York can deliver to every neighborhood new open spaces that will reduce traffic violence, asthma, and pollution while providing flood-mitigating climate resiliency.

“Open Streets have been the best part of life in Brooklyn since it started. It's fantastic.”

The City of New York is itself a best practice example of this process of returning streets to people: Central and Prospect parks, which were once full of car traffic, are now permanent Open Streets. Almost all large-scale housing projects across New York City — from Stuyvesant Town to Co-Op City — are filled with permanent Open Streets, where residents thrive even though they cannot drive a car up to their front door. In the Financial District, narrow Stone Street allowed car traffic in the 1990s but is now a permanent Open Street, and Fulton Street in that neighborhood is a permanent Open Street of food trucks serving office workers. In the East Village, there are several permanent Open Streets, including one that’s been around for more than 60 years. West 33rd Street in Midtown was once congested and polluted; same for East 91st Street on the Upper East Side. Now both are permanent Open Streets, with plans underway to improve West 33rd Street even more.

Street Design

Open Streets cannot be monitored at every hour of the day, so the City of New York should redesign Open Streets to discourage driving and calm traffic. The redesign of Open Streets should include the reduction or elimination of on-street parking, and the installation of a variety of permanent bollards, barriers, and curb extensions, including chicanes, bus bulbs, and pinch points, using bike parking, bioswales, and street trees. This will discourage driving on Open Streets, control local traffic speeds to five miles per hour, and open up more space and visibility for pedestrians at the crosswalk. Examples of these permanent street redesign methods to discourage driving can be found employed throughout the world, including very recently on 39th Avenue in New York City, the first Bike Boulevard.

The City of New York should also work with the New York State legislature to pass a law limiting driver speeds to five miles per hour on all Open Streets, add permanent signage indicating this limit, and install automated enforcement to ensure that no one drives down an Open Street at an unsafe speed.

On part-time Open Streets, midblock crosswalks and curb cuts should be installed to create multiple points of accessibility. On full-time Open Streets, curbs should be eliminated — also known as a Woonerf, an entirely curbless street used to calm traffic and encourage walking, seen in Denmark, Germany, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. A woonerf puts the street and sidewalks all on one level, and thus entirely accessible to people who use wheelchairs, rather than via solitary curb cuts at the beginning and end. On both varieties of Open Streets, the color of the pavement should be altered to create visual cues indicating the Open Street, such as on Broadway and 25th Street in Manhattan.

Credit: Sam Schwartz Engineering

Length

The City of New York should also lengthen all Open Streets to a minimum half-mile, which TA research shows is the optimal minimum for visitor enjoyment. Longer Open Streets were consistently rated higher by surveyors. Longer Open Streets also add more functionality: creating public space for recreation while also acting as a safe addition to the bike network.

“It’s like an oasis.”

While the surveyors’ data in this report indicates that longer Open Streets are significantly more popular, it is not hard to find other proof that length has a positive effect on car-free open spaces. For example, perhaps the two most beloved Open Streets in New York City, the Central Park and Prospect Park loops, are each over three miles long. The 34th Avenue Open Street in Queens, which is perhaps the most well-attended of any in the current program, is also one of the longest at 1.2 miles. This is true elsewhere, as well: a 2012 guide to Open Streets from the National Association of City Transportation Officials clocks the average length of Open Streets in North America at nearly four miles long.

Barricades

Credit: Reilly Owens

Today, Open Streets’ barricades are inconsistent in design, placement, and responsibility. However, when effective barricades are available and placed to deter driving, they keep Open Streets safe and clear of unnecessary vehicular traffic. In making the Open Streets permanent, these barricades, too, must be permanent and largely immovable. Such materials will reduce the amount of community involvement required to set up and take down barriers, lower the threat of traffic violence, and increase the usage of Open Streets for all purposes.

The majority of Open Streets should be permanent, 24/7 public spaces. For these Open Streets, the City of New York should install permanent infrastructure for filtered permeability, as is already done in on many pedestrianized streets, using bollards or boulders, located in a way that blocks driving entirely or requires drivers to slow to five miles per hour, eliminates parking outside of limited loading zones, and limits on-street access to residents and deliveries.

For part-time Open Streets, which should be an interim measure on the way to creating permanent Open Streets, the City of New York should create wheeled barricades, using planters or other sizable, moveable, but not easily stealable materials. Planters make optimal temporary barricades, whether wheeled and movable or stationary, adding greenery to asphalt-filled spaces, cleaning the air, and cooling the pavement. The City of New York must also create a uniform barrier and signage system that makes clear what is a car-free Open Street.

There are already several Open Streets in New York City that use exemplary barricades. Jay Street at MetroTech is a permanent 24/7 Open Street protected by metal bollards. Near New York University, what used to be Wooster Street is now a permanent 24/7 Open Street protected by metal bollards. And on what used to be Cortland Street is now another metal-bollard-protected permanent 24/7 Open Street.

Equity

“I have low vision, to be able to walk on the street with space and few cars feels so freeing and safe.”

The longest, safest, best-protected, and highest-rated Open Streets in New York City should be in the neighborhoods with the least green space, the highest asthma rates, the worst congestion and air quality, and the most dangerous streets. Today, the opposite is true.

Open Streets are inequitable because New York City is inequitable. If an Open Streets program relies on volunteer support, then Open Streets will be better in neighborhoods where residents are rich in free time and worse in those without such luxuries. If the Open Streets program fails to make any infrastructural changes to the streetscape, then in neighborhoods where reckless driving is already rampant or air quality is already low, Open Streets will be threatened by reckless drivers and of little use to those for whom poor air quality is a threat. A simple barricade cannot solve structural problems. To make Open Streets fair, the City of New York needs to actively and aggressively invest in making streets fair.

The City of New York should aggressively fund Open Streets with equity as a focus, targeting and distributing resources to the neighborhoods with the greatest need: the highest rates of asthma and the worst air quality, with the greatest burden of traffic fatalities and injuries, with the least green space and where income equality and historically racist planning policies have otherwise left residents at a disadvantage. A positive example of this practice comes from the metrics that the DOT uses to place public pedestrian plazas: heat-mapping income, open space access, and traffic violence.

To find out where Open Streets are most needed, the City of New York should conduct a citywide infrastructure audit that tracks historic and modern spending on city streets by neighborhood, overlaid with rates of speeding, traffic violence, asthma, air quality, and access to green space. With this audit, and these problems mapped, the City of New York can plan, prioritize, and fund Open Streets to directly respond to these problems. The City of New York should then track the success of Open Streets by tracking these metrics and report this data annually.

“It felt amazing to see older people, a couple, a parent with a stroller, and people biking. There was a warm sense of camaraderie — all those walking smiled & nodded/said hello to each other, not common in this neighborhood.”

The City of New York should be the primary caretaker of Open Streets — not volunteers, even in time-rich neighborhoods. However, where the City is unable, it should create and fund an Open Streets Caretaker program, which pays local businesses, community organizations, and residents to set up and dismantle Open Street barricades, pick up litter, and solve other maintenance issues. The Horticultural Society of New York’s City CleanUp Corps provides an excellent model. To aid these Open Street Caretakers, the City should install a storage container in a parking space, in which the community can store supplies as well as create a pool of borrowable chairs, tables, and games to activate the space.

The built-in inequities that make Open Streets less functional and hospitable in neighborhoods where there has been historic underinvestment in infrastructure also extend to the presence of Open Restaurants. This program is less effective in neighborhoods with few street trees, excess litter, and bad traffic congestion, or for restaurants that are financially strapped and cannot build out the required infrastructure. To that end, the City of New York should plant more street trees, create an on-street containerized trash system, and expand car-free busways, starting with the neighborhoods where heat island effects, pollution, litter, and congestion are worse. The City should also create an interest-free loan or grant program for restaurants in these neighborhoods to create shaded on-street restaurant space.

It is also critical that the Open Restaurants program — which provided free land use to New York City’s restaurants as a path to reopening during the coronavirus pandemic — not limit or block the public from access to public space. The City should also require and enforce the ADA-accessibility requirements of an eight-foot clear passage of space for all street users, even when outdoor dining is in place. When the coronavirus pandemic passes, Open Restaurants should remain and pay a fee for use of public space. Those fees should be dedicated to improving public spaces across New York City.

Policing

According to those individuals with perhaps the greatest understanding of how Open Streets function — the volunteers who set up barricades, clean up litter, and plan programming at their Open Streets — there have been challenges between the New York Police Department (NYPD) and Open Streets.

“I love Open Streets and I particularly like the culture that's being cultivated there. It's becoming a genuine community space. There are some legitimate concerns about accessibility with barriers particularly, but these seem like solvable problems that can easily be fixed with a permanent redesign of the street.”

For example, volunteers on one Open Street reported that, on more than one occasion, the nearby NYPD precinct diverted traffic onto the active Open Street, so pedestrians had no idea that dangerous traffic was coming up behind them. Volunteers on another Open Street reported that, on more than one occasion, the local NYPD precinct refused to ticket or tow vehicles illegally parked on the Open Street during permitted events there. At others, police officers appeared to have little understanding of the purpose or rules related to Open Streets, and as result, often directly affected the ability of the Open Street to function.

The DOT, and not the NYPD, should continue to manage this program. The City of New York should also inform all City agencies, especially the NYPD, as to how Open Streets function, and that agency’s role in the program, including the necessity of clearing the street of parked cars, and how to avoid putting people using the Open Street at risk. Whatever day-to-day staffing requirements are necessary for Open Streets management should come from City employees, and budgets should be adjusted accordingly to fill that need.

Legislation

In 2020, at the behest of the New York City Council, Mayor de Blasio promised to deliver to New Yorkers 100 miles of equitably distributed, active Open Streets. This pledge was based on a desire for New York City to host the largest Open Streets program in the U.S. The City of New York should meet this promise and make this ambition a reality.

In 2021, the City Council passed, and Mayor de Blasio signed, legislation that requires the City of New York to plan, create, staff, and manage at least 20 Open Streets. That legislation also required the DOT to provide signage, street furniture, and more to Open Streets organizers citywide; allowed the DOT to approve 24/7 Open Streets; permitted community groups to request parking space removal to aid Open Streets; allowed for the addition of infrastructure significant enough to make barriers obsolete; and asked the DOT to consider street design changes to make Open Streets work better. The City of New York should act with urgency to meet the requirements of this legislation, which goes into effect in October 2021, and take advantage of the vast potential of what this law allows.

Low Traffic Neighborhoods

By and large, New York City’s residential streets look identical: two lanes of parked cars and a lane or two for vehicle travel. However, car-ownership rates in New York City’s residential neighborhoods fluctuate wildly, from 18 percent of residents in large swaths of Manhattan to 92 percent of residents in southern Staten Island. To boost the effectiveness of Open Streets in those neighborhoods with the lowest rates of car ownership, the City of New York should pioneer New York City’s first Low Traffic Neighborhoods.

Low Traffic Neighborhoods are groups of residential streets, typically adjacent to arterial roads, where automated enforcement, infrastructure, and signage is used to discourage through traffic. While residents of these neighborhoods can still run errands using vehicles, there is less traffic passing through their neighborhoods, while reducing air pollution and traffic violence, and increasing community and physical activity.

While the absence of barricades on Open Streets almost guaranteed intrusion by cars, 29 percent of those Open Streets with no barricades saw five or fewer cars in five minutes. Arguably, these neighborhoods are already “low-traffic,” but because when that one car intrusion occurs, it occurs at 25 to 30 miles per hour, the otherwise empty street is unsafe to use.

When neighborhoods in outer London implemented Low Traffic Neighborhood programs, car ownership decreased, as did weekly car use and the number of minutes spent driving, while physically active transportation rose. Crime fell significantly in the Low Traffic Neighborhoods, especially those crimes that involve a direct attack on a person: violence and sexual offenses, but property damage, weapons possession, burglary, and vehicle crimes all fell, too. In London’s Low Traffic Neighborhoods, pedestrian injuries fell by half.

School Streets

The City of New York should respond to the latent and growing demand for School Streets as a new school year begins with the Delta variant raging and still no vaccine available for most school-age children. The City should close a one-block stretch of the street outside every New York City school to cars and open the space to schoolchildren.

School Streets can do more than make for a more COVID-19-safe learning environment. Closing streets to cars to make space for school use can reduce pollution and traffic violence, encourage active play, and improve asthma rates. There are cognitive disadvantages to pollution, so School Streets can even improve students’ ability to learn.

Traffic violence is the number one cause of injury-related death for school-aged children, and the average elementary-age child lives within one mile of more than 13 schools. (This number is even higher for low-income children and children of color.) More than one in five New Yorkers is of school-age or younger, giving this program a remarkable cost-benefit effect in terms of population served. Three out of four school-aged children in New York City are not driven to school, and more than one in three walks. New York City high school students report riding a bicycle at least once a month — nearly twice the rate of New York City adults. The potential benefits of reclaiming car space to give to these children are endless.

“Raining and still packed.”

Similar programs have been used to combat earlier viral epidemics in New York City and are currently helping students learn is a safe, outdoor, less polluted environment in Milan, Barcelona, Seattle, Vancouver, in Paris, which hosts 185 School Streets, and in the United Kingdom, in London, Edinburgh, Camden, and Hackney. Some New York City schools, such as PS 11 in Chelsea, have been operating a School Street for at least a decade.

Car-Free Halloween, Air-Quality Alert Days, and Other Special Occasions

New York City’s streets are not static objects. Rather, as traffic ebbs and flows, it interacts with other factors, both environmental and circumstantial. For example, on hot summer days, New York City’s traffic-induced air-quality issues are exacerbated, resulting in Air Quality Alert days, which result in increased asthma-related hospitalizations. Or, on Halloween, New York City’s pedestrian- and car-dense streets are even more crowded, resulting in a rise in child-pedestrian fatalities.

On these needful days, the City of New York should use Open Streets as a tool to respond to immediate and planned demands for car-free open space. On Air Quality Alert days, on Halloween, and on gridlock alert days (like when the president is in town or the United Nations is in session), the City of New York should expand Open Streets to provide car-free transportation networks, clean-air pocket parks, and grand trick-or-treating thoroughfares.

Other Recommendations

“Late afternoon on Sunday there were parents and kids on bikes, walking and playing games. There were adults eating and drinking and standing in the street socializing. It was a wonderful experience.”

Between the City of New York’s Open Streets program, Play Streets program, Pedestrian Plaza program, Outdoor Learning, and Shared Streets programs, New Yorkers who wish to reclaim local street space from cars face confusing bureaucratic overlap. The purpose and goal of these programs are the same — to transform underutilized street space into space for people. The City of New York should combine these programs to create a unified location for budget allocations, interagency cooperation, and community and resident requests.

The City of New York should also use Open Streets to incentivize Farmers Markets in fresh food deserts. New York City’s food deserts also happen to be located where the fewest Open Streets currently exist.

The City of New York should also work with mapping apps to both route drivers away from Open Streets and direct people walking and biking toward Open Streets. Including Open Streets on New York City’s Bike Map and in bike open data will aid this.

Methodology

Survey

This report is based on publicly available information from the New York City Department of Transportation (DOT) and the survey results collected by Transportation Alternatives (TA) volunteers between June 24 and August 21, 2021, using Google Forms. A total of nearly 791 survey results were collected, including at least one survey from all 274 Open Streets in New York City, by more than 350 unique volunteers.

Active / Listed

An “active” Open Street is defined as an Open Street where at least one surveyor observed barricades in the street, during the hours and days listed by the DOT, even if this survey result was contradicted by other survey results. A majority of Open Streets were surveyed more than once, and nearly all Open Streets that had barricades, but not in the street, were observed more than once. Otherwise, an Open Street was considered “non-operational,” meaning no surveyors ever saw any barricades present on any visit. What constitutes a “listed” Open Street, as well as listed Open Street length and mileage, is based on the Open Streets listed and publicized by the DOT. Open Streets that were shorter in real life than what was listed by the DOT were counted as their listed, not actual, length. Open Streets that were active in real life but not listed by the DOT were not counted. (We will not name these for fear of generating undue attention to any community members who may be reclaiming their streets in an unauthorized fashion.)

Ratings

The Open Street “ratings” referenced in this report are based on surveyors' opinions as to how inviting an Open Street felt on a scale of one to 10. For average citywide and borough-wide ratings, each Open Street was weighted equally, regardless of how many survey responses there were for any given Open Street. This was done by calculating the average of the survey responses for every Open Street individually and then averaging all the Open Streets for a given area (e.g. citywide or borough-wide) equally. This was done to prevent over-representation from Open Streets with higher participation rates.

Delisted and New Open Streets During the Surveying Period

Several Open Streets were officially dismantled and delisted by the DOT during the program and the surveying period. These were removed from TA’s surveying program as soon as TA became aware that the Open Street had been dismantled. However, the DOT never announced when Open Streets were taken offline, so we cannot be sure if surveys about these Open Streets were submitted when an Open Street was taken offline and before TA became aware of it. Since the reporting period's ending in August, more Open Streets have been both delisted and added. This report is based on the conditions on the ground between June 24 and August 21, 2021, only.

Demographic Data

Demographic data on which New Yorkers live near Open Streets was pulled from the New York City Department of City Planning’s Population Factfinder, which is based on 2014-2018 American Community Survey (Census Bureau) results. Detailed 2020 Census Data is unavailable to the public yet, but the disparities outlined in this report may be exacerbated even further if the new Census data was used instead. All census tracts fully and partially located within a 0.25-mile radius from all points of an Open Street were included in the analysis as “walking distance.” Although this method includes New Yorkers outside the 0.25-mile radius of an Open Street, nearly all parts of every Census Tract fall within 0.75 miles of the Open Street. An analysis was then conducted on race, ethnicity, and income.

Miscellaneous DOT Data Issues