Big Ideas to Make Buses Fast

New York City’s buses are the slowest in the nation — but they don’t have to be. With a few low-cost changes, we could not only improve this dismal ranking, but also have buses that are downright fast.

All it will take is a few big ideas …

Why Do Fast Buses Matter?

New Yorkers walk faster than most other people — over 4 mph on average. Which means, depending on the time of day, you may be walking faster than the bus in places like Manhattan’s Community Board 11, Brooklyn’s Community Board 9, and the Bronx’s Community Board 2, where bus speeds average between 4 and 6 mph.

And while that’s comically slow, the missed potential is no laughing matter. Just a 15% increase in bus speeds could save the MTA $268 million per year — and that money could be invested in everything above, expanding service, making buses faster and growing ridership.

"Just a 15% increase in bus speeds could save the MTA $268 million per year."

And it’s about more than money. Consider the results when we prioritize bus riders, like on the car-free 14th Street Busway. Travel time fell by 47% and ridership rose 17% in just two months, so much so that the City needed to purchase additional buses. When congestion pricing sped up buses by removing 67,000 cars from the road daily, the MTA expanded bus service on 16 routes, and now riders have faster and more reliable commutes.

These gains would be extraordinary if spread citywide. London’s red-painted and camera-enforced bus lanes make up only 5% of the city’s road space but carry 35% of its traffic.

And there couldn’t be a more important population to prioritize. Bus riders have substantially lower median incomes than those of subway riders or New Yorkers overall, are less likely to have a bachelor’s degree, more likely to be a single parent, more likely to be foreign-born, more likely to be a person of color, and more likely to have a child at home.

In New York, a lack of access to good transit is correlated with lower median incomes and higher unemployment. The Pratt Center found that 750,000 New Yorkers commute longer than an hour each way, and two thirds of these commuters earn less than $35,000 a year. A mere six percent of those long commutes are made by those earning more than $75,000 a year.

The big idea? Faster buses are good for New York.

24/7 Bus Lanes

Buses aren’t slow; traffic congestion is. That’s why car-free bus lanes dramatically improve bus speeds — like the car-free busway on 14th Street, which reduced travel times by 47% after installation.

But today, many New York City bus lanes have a time limit that minimizes their effectiveness. Buses run 24/7, but close to 40% of dedicated bus lanes are only in effect for certain hours. It’s a confusing hodgepodge: some lanes are 24/7, others operate from 7 a.m. to 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. to 7 p.m. on weekdays, and still others are car-free from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m., seven days a week. It’s tricky for drivers to navigate, unpredictable for bus riders, and it’s keeping buses slow — especially for the typically low-income, hourly workers who clock weekend and overnight shifts.

The big idea? The City of New York should convert all dedicated bus lanes to 24/7 operation.

Car-Free Busways

Car-free busways give buses exclusive access by moving all but local car traffic to adjacent streets. This can work wonders to improve bus speeds — like the car-free busway on 14th Street, which reduced travel times by 47% after installation.

But there are few busways in New York City, just a stack of approved plans to replicate the project, all stalled in political limbo.

There are busway plans currently sitting on the shelf — planned and approved, but not yet implemented — for 34th Street and 5th Avenue in Manhattan, Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn, and Fordham Road in the Bronx.

The big idea? Make all these busway plans a reality.

Enforcement Cameras and Red Paint

While bus lanes provide an expedited path, those lanes operate more efficiently with a few enhancements: enforcement cameras and red paint. Let’s run through them.

First, cameras. The City of New York has the authority to use automated, bus-mounted cameras to enforce against drivers parking in the bus lane.

Where in use, they’re effective: camera-enforced lanes have helped to increase bus speeds and reduce collisions.

"Camera-enforced lanes have helped to increase bus speeds and reduce collisions."

The same is true — surprisingly — of simple red paint. After San Francisco painted bus lanes red, the number of cars in the bus lane fell by half. Baltimore reported faster buses on nearly all routes where bus lanes were painted red. But today, while some of New York City’s 160-odd miles of bus lanes are demarcated with red paint, not nearly enough are — despite the fact that painting a bus lane red is cheap, easy, and can significantly improve bus speeds.

These simple tweaks transform the basic bus lane into a protected passageway, giving the bus the fast lane it deserves.

The big idea? Every bus lane in New York City should be protected with automated enforcement cameras and demarcated with red paint.

Priority Signals

Priority signals are perhaps the most straightforward route to faster buses, giving buses the green light wherever they go. Here’s how it works: When a bus is approaching an intersection, a beacon on the bus communicates with a sensor in the traffic signal. The signal will then extend the green light or shorten the red to give the bus priority passage through the traffic light.

But today, while many bus lanes have priority signals, nowhere near every bus route is covered. While every bus route should ideally have a bus lane of its own, until that happens, expanding priority signals to bus routes without bus lanes could go a long way to giving the bus the green light.

The big idea? Every intersection on every bus route should be equipped with a transit signal priority system.

Bus Bulbs and Curb Management

Double parking in curbside bus lanes is a disaster for the bus, but if we just blame the double parkers, we miss the forest for the trees. Despite New Yorkers’ increasing reliance on for-hire vehicles and goods delivered to our doors, we have made few accommodations for truck and taxi drivers to access the curb. One study of commercial vehicles found that cruising for parking accounted for 28% of total trip time. It’s no wonder they park in the bus lane.

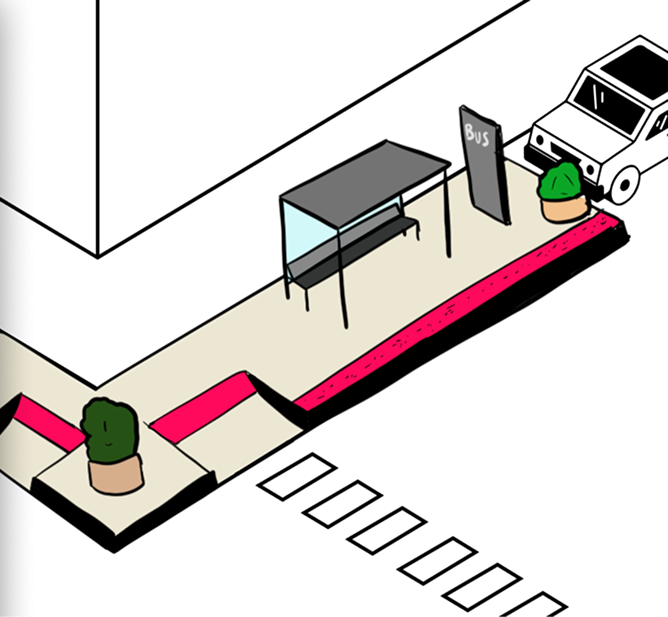

The solution is to protect the bus lane while providing for those double parkers by moving the bus lane off the curb and installing bus bulbs.

A bus bulb is a small concrete curb extension that can do a lot. It improves bus speeds by eliminating the need for the bus to weave in and out of traffic. It helps waiting riders be more visible to bus drivers. It protects the bus lane from double parking. It instantly creates a curbside loading and drop-off zone that’s in another lane and out of the way of the bus. Bus bulbs even expedite bus boarding by allowing the bus to be level with the curb — helping people with disabilities and everyone else to roll or walk right on.

This simple change also has a benefit that has nothing to do with speed. Bus bulbs make space on the curb for bus shelters and benches — which doesn’t make the bus faster, but does make riding it a lot nicer.

The big idea? Install bus bulbs at every bus stop in New York City.

Tunnels, Bridges, and Highways

New York City’s tunnels, bridges, and highways provide an opportunity to expedite buses with protected express lanes. While a typical traffic lane carries about 3,000 people in 2,000 cars each hour, an express bus lane can carry over 30,000 people in 700 buses during that same time period.

The big idea? Use jersey barriers to create 24/7 protected express bus lanes on every New York City bridge, tunnel, and highway that hosts a bus route.

All-Door Boarding

A significant and surprising time-suck on New York City’s bus routes is the simple act of getting on board and paying the fare. Gathering exact change, finding your OMNY card, waiting in line, or navigating a broken fare machine may take minutes, but when it happens at every stop, those minutes add up. And despite the fact that most buses have two doors, the MTA prohibits anyone from boarding in the back, which means bus boarding takes twice as long as it needs to.

"All-door boarding has been shown to significantly improve bus speeds."

All-door boarding has been shown to significantly improve bus speeds where it has been tested in New York City and generally increases ridership and reduces congestion wherever it’s implemented. A “free bus” pilot program had similar results, increasing ridership and improving bus speeds. One study estimated that free buses citywide could increase average bus speeds by at least 12%.

Making buses free will require a revenue replacement for missing fares, but combined with all-door boarding, it would shave off serious time at every bus stop. These simple tweaks transform the basic bus lane into a protected passageway, giving the bus the fast lane it deserves.

The big idea? Implement all-door boarding and find a revenue replacement to eliminate the fare.

Free Transfers

New York City has a lot of ways to get around — but most of them require a second fare. While you can transfer for free from the bus to the subway, you can’t hop on a Citi Bike, the ferry, the LIRR, or Metro-North without paying another fare. Multimodal fare integration has been shown to increase transit ridership and shift trips out of cars — and fewer cars means faster buses.

The big idea? Coordinate the MTA, NYC Ferry, and Citi Bike to create an integrated multimodal fare.

Discounted Commutes

Today, thousands of New Yorkers receive parking subsidies from their employers, encouraging them to drive to work instead of taking transit. But the more people who drive to work, the more congested the streets are, and the slower buses run. Other cities have solved this problem by giving employees the choice of receiving the parking benefits or a cash equivalent — allowing them to “cash out” those parking benefits to use for more sustainable forms of transportation.

Permitting New Yorkers who bike, walk, or take public transit to work to “cash out” the funding that their employers provide for parking as a reward for choosing green transportation would reduce congestion and grow bus ridership. A study of one commuter benefits “cash-out” program found that, as a result, solo driving to work fell 17%, carpooling increased 64%, transit ridership increased 50%, and walking or biking increased 39%.

The big idea? Shift commutes out of cars and incentivize public transit by giving commuters a new way to pay for the bus.

Countdown Clocks

Knowing when the bus is coming doesn’t make the bus come any faster, but interestingly, it does make it feel like the bus is coming faster. Researchers have found that perceptions of how long it takes for the bus to come are dramatically reduced when riders are made aware of how long the bus will be arriving. Researchers studying countdown clocks on the New York City subway have also found that countdown clocks can increase ridership.

The City of New York has already been piloting affordable, easy to install touchscreen countdown clocks on some Upper West Side buslines.

The big idea? Every bus stop gets a countdown clock.

More Routes, More Lanes, More Service

Today, just over 2% of New York City streets have bus lanes. The best way to make buses faster is to plan more bus routes, build more bus lanes, and increase service on existing ones.

And there’s a wealth of ways to approach this idea. We could tackle the top ten, building bus lanes on the ten routes with the highest ridership and slowest speeds. We could expand capacity by doubling the width of bus lanes on the most trafficked existing bus routes. We could even take advantage of the space freed up by congestion pricing to build New York City’s first bus rapid transit routes — gold standard bus lanes that incorporate many of the idea above, including bus bulbs, red painted lanes, camera enforcement, all-door boarding, and transit signal priority, to make the bus run as efficiently as the subway.